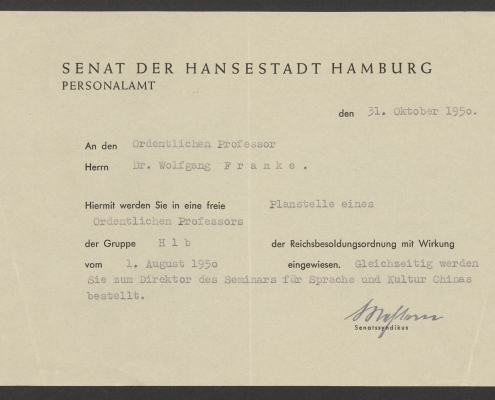

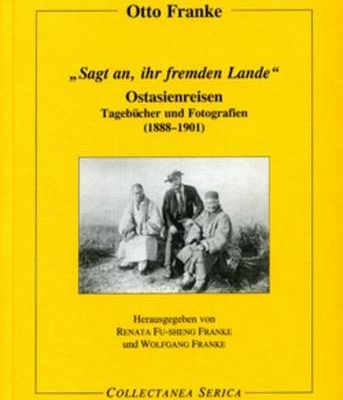

For the winter semester of 1950/51, Wolfgang Franke took over the professorship of Sinology at the University of Hamburg, a position previously held by his father, Otto Franke, from 1910 to 1923. Franke became the director of the Seminar for Language and Culture of China (1950-1970) and played a crucial role in the re-establishment and further development of Sinology in Germany until his retirement in 1977.

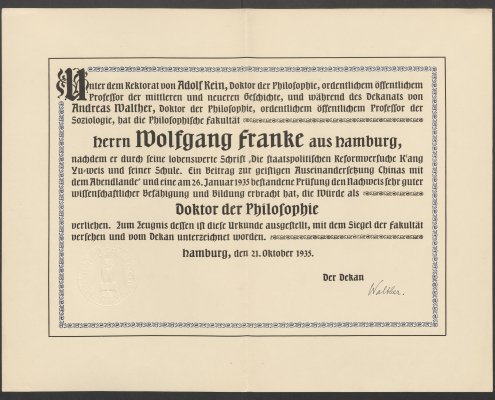

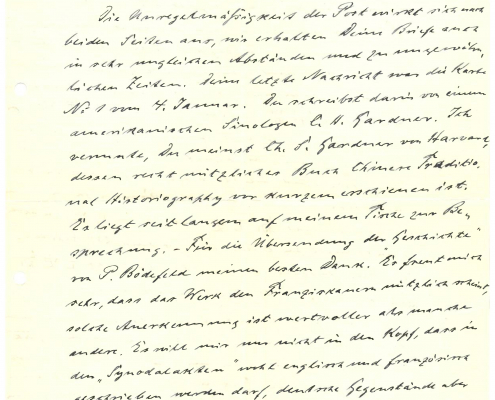

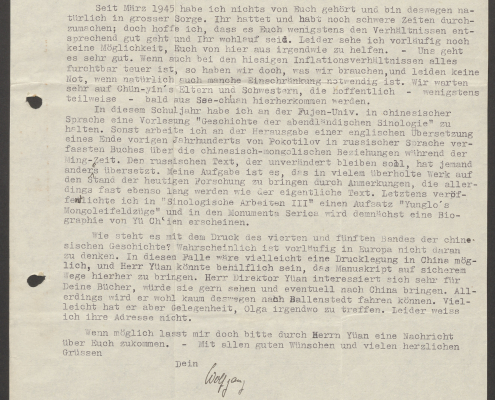

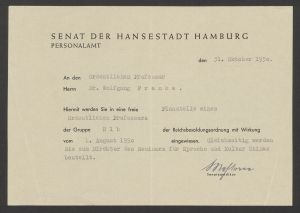

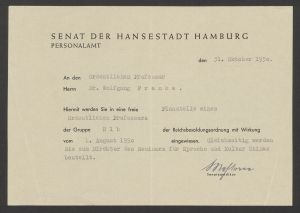

Wolfgang Franke’s appointment certificate (1950)

At the end of World War II, German Sinology was largely in ruins. Many libraries had been destroyed, and there was a scarcity of qualified personnel untainted by the past to rebuild the discipline. For Franke, as a chair holder, it was an urgent task to reconstruct the subject in its institutional structures and later to expand it. In this context, the creation of a second professorship for Sinology in Hamburg was of particular importance: in 1967, it was possible to appoint Liu Mau-Tsai (1914–2007), the first Chinese scholar to a sinological professorship in Germany. He complemented the Hamburg Sinology with a focus on Chinese literature.

During his tenure as a chair holder in Hamburg, Franke took advantage of the diverse opportunities and freedoms available to him as a professor. He spent extended periods on research stays and held visiting professorships in Japan, the USA, Malaysia, and, after his retirement, also in China. Meanwhile, he was represented by renowned international colleagues, which gave the Hamburg Sinology a special flair in the post-war period.

In his research, Franke focused intensively on the Ming Dynasty from the 1940s onwards. His initial goal was to fulfill his father’s wish and continue his “History of the Chinese Empire” for the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Although Franke reluctantly abandoned this project in the 1960s because he did not share his father’s state-political view of history, influenced by the Prussian school of historicism, he continued his sinological source collection and historical research on Ming China in a variety of contributions. This focus ultimately became influential in shaping the field: the majority of his students engaged in their qualification theses with historical and specifically sinological aspects of the rich history of the Ming – which also received broad international resonance.

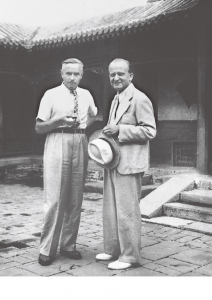

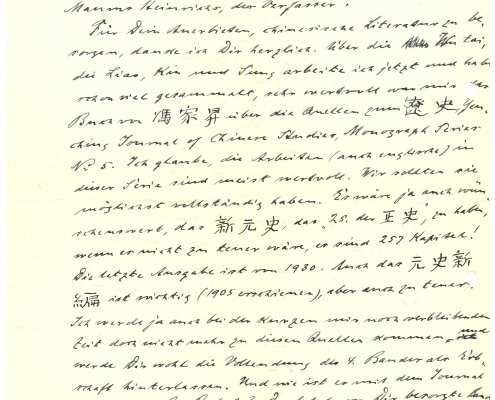

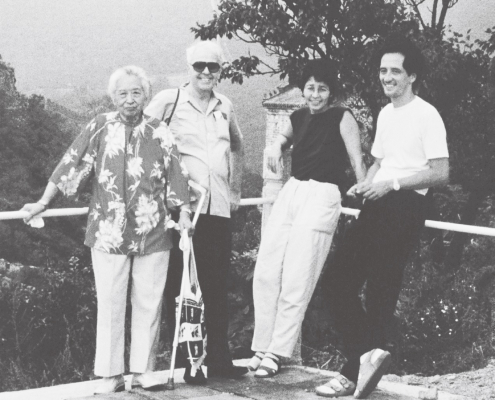

Wolfgang Franke with graduates of the Department of Chinese Studies in Kuala Lumpur (1970s) ©unknown

From the late 1960s, Wolfgang Franke’s central research interest became the study of the history of overseas Chinese in the Southeast Asian region. In 1963, he was offered a visiting professorship at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Over the next three years, he taught Chinese history there and further developed the newly founded Department of Chinese Studies. The stay in Malaysia not only allowed him to live in a Chinese environment while the People’s Republic of China was still largely isolated, but it also gave him the opportunity to meticulously collect epigraphic material on the history of the overseas Chinese who had been living there for centuries. The study of the history of overseas Chinese in the Southeast Asian region became Franke’s new research focus from the late 1960s, which was supported by the DFG (German Research Foundation) from 1971 to 1974. After his retirement in 1977, Franke spent most of the year in Malaysia, which had become a second home for him. In the 1970s and 1980s, he undertook numerous trips through many countries of Southeast Asia; the fruits of this field research, a vast collection of epigraphic material, were published in the 1990s in the form of several source volumes. In the study of the history of overseas Chinese in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, these works are now considered essential reading.

Unlike the majority of German Sinology from the 1950s to the 1970s, Wolfgang Franke’s work was also characterized by a dedicated focus on modern China.

In 1935, Franke earned his doctorate with a thesis on Kang Youwei’s reform attempts in the final years of the Qing Dynasty. Even in the post-war period, he extensively engaged in the younger Chinese history and the Sino-Western relationship through monographs and journal articles. Noteworthy are his study “Das Jahrhundert der chinesischen Revolution 1851-1949” (1958) and his work “China und das Abendland” (1962), both of which were translated into English and established Franke as a significant cultural broker in the contemporary popular discourse on China.

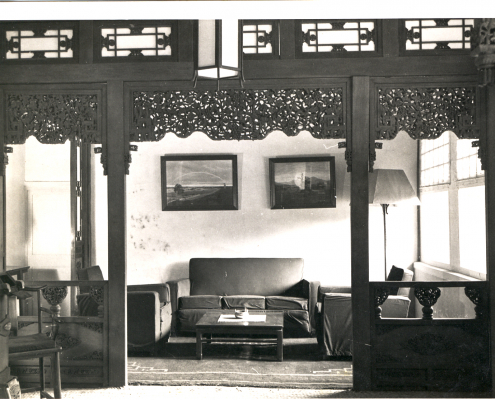

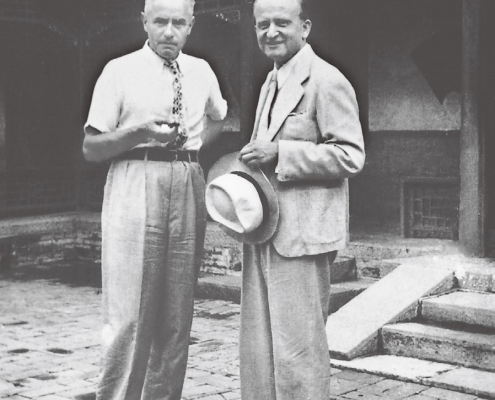

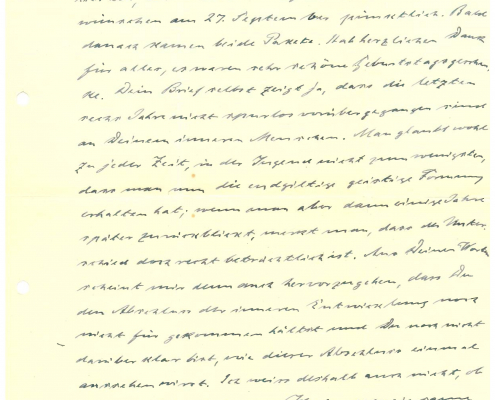

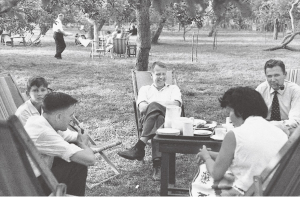

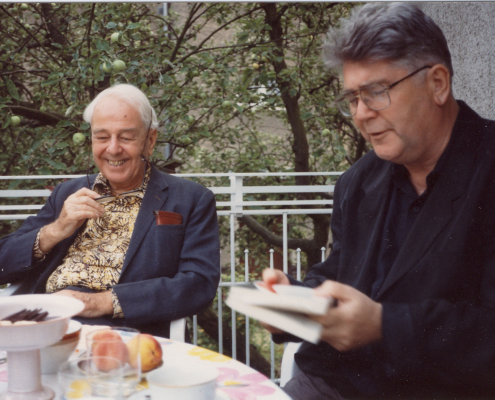

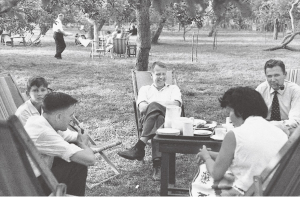

Wolfgang Franke and the Sinologist Eduard Solich (1893-1982) at the East Asian Banquet in Hamburg (1950s) ©unknown

His extensive commentary on these topics, however, was not because Franke was particularly political—in his autobiography, he even describes himself as apolitical. Rather, the reading of his autobiography and interviews with his contemporaries gives the impression that, on one hand, Franke was convinced that understanding contemporary China and its relations with Western societies was impossible without engaging with its recent history. On the other hand, he saw the urgent need for intercultural mediation between China and Western societies to enhance the understanding of the “other”. Precisely for this reason, Franke advocated for a concept of Sinology that focuses on the history, society, and everyday culture of a modern China, rather than dealing exclusively with classical texts philologically. This approach is particularly evident in the highly acclaimed “China Handbuch” of 1974, which he compiled with his former student, sinologist Brunhild Staiger (1938-2017), gathering over 130 authors who contributed more than 300 short articles on various aspects of China since 1840.

The publication of the China Handbuch under the auspices of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasienkunde (DGOA) exemplifies Franke’s role not only as an international research figure but also his engagement in various institutions and committees. Besides the DGOA, the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Volkswagen Foundation are particularly worth mentioning. Franke placed special importance on the Institut für Asienkunde (IfA) in Hamburg, which, since the late 1950s, served as a non-university research institute funded mainly by the Foreign Office, providing relevant studies on contemporary China and the Southeast Asian region. For several decades, he was a member of the institute’s board and collaborated with its staff in teaching and research.

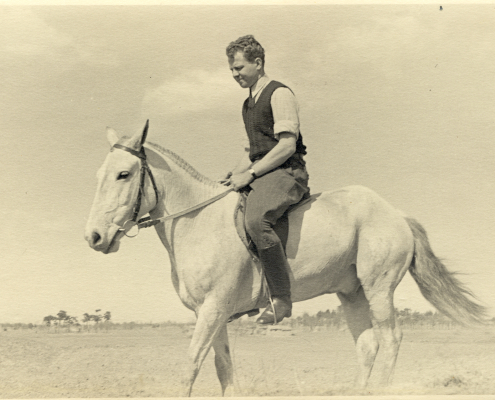

Wolfgang Franke at the Junior Sinologists Conference in England (1959) ©unknown

Franke’s commitment to intercultural brokerage is further evidenced by the emphasis placed on learning modern Chinese colloquial language at the sinological seminar. Well into the 1960s, Hamburg’s Sinology was the only seminar nationwide that began studies with modern Chinese and taught classical written language later. Beyond the confines of his seminar, he advocated for the inclusion of modern China as an integral part of Sinology studies at universities.

Franke’s multifaceted engagement with contemporary China and his intercultural efforts in public discourse, not least through relevant China booklets for the Federal Agency for Civic Education and its predecessor, made him a sought-after consultant in political contexts. Franke’s advisory role to the planning staff of the Foreign Office on initial considerations for a German East Asia policy in the late 1960s, as well as his role as a consultant to Walter Scheel in the context of establishing diplomatic relations in the fall of 1972, can certainly be considered two of the most important episodes.

Schütte: China (2016) ©Karl Baedeker Verlag

However, Wolfgang Franke was not only a significant research figure and a cultural broker between East and West; he was also an academic teacher whose students went on to become renowned professors, including Tilemann Grimm, Bernd Eberstein, Boto Wiethoff, Monika Übelhör, and also Manfred Pohl in Japanese Studies.

Notable personalities who consciously chose against an academic career also emerged from Hamburg Sinology. A prime example is the sinologist and publicist Hans-Wilm Schütte (1948-), who earned his doctorate under Franke in the late 1970s on Marxist historiography in the People’s Republic of China. In the following decades, he became one of Germany’s most-read China publicists through his travel literature.

Franke’s impact and achievements are challenging to summarize succinctly; nonetheless, publicist Hans-Wilm Schütte managed to do so in an interview with the authors:

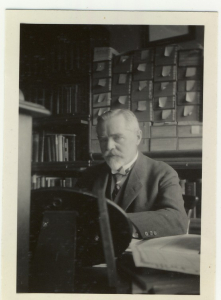

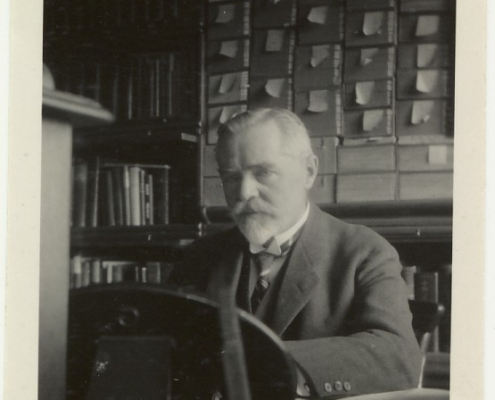

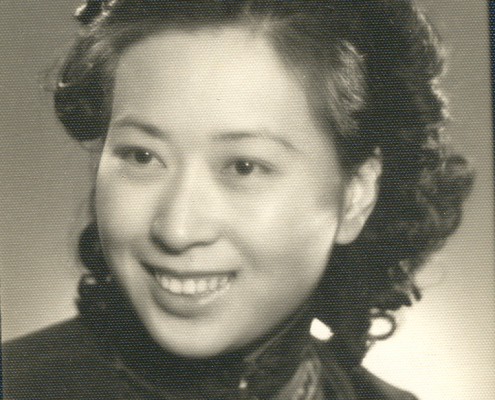

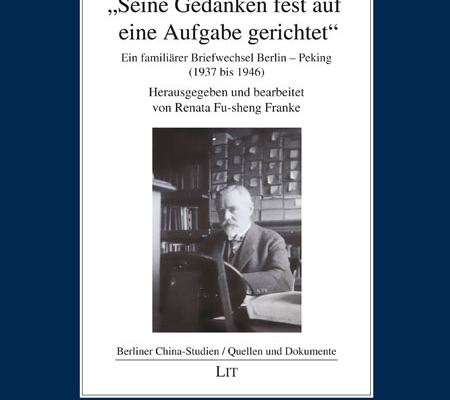

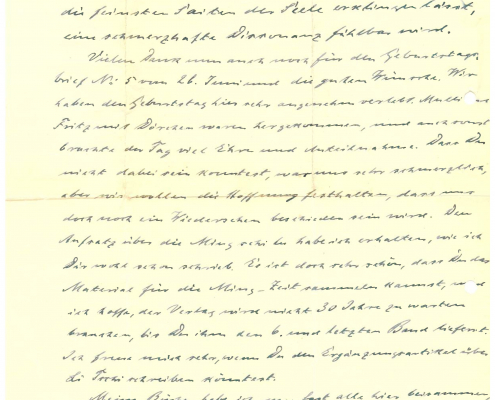

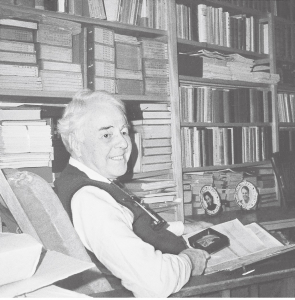

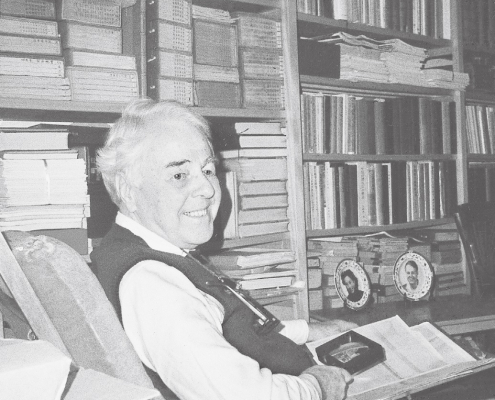

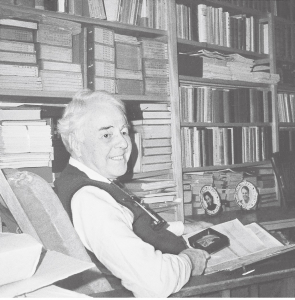

Wolfgang Franke in his study (1986) ©unknown

“Many foreigners live in China for years but only learn as much Chinese as they need for daily life and never learn to write and read Chinese. Back home, they are considered experts on China, although they are not. Wolfgang Franke’s stay in China, thanks to his language skills, gave him a familiarity with the country and its traditions like few others had at that time (in the fifties to seventies).

This combination of scholarly depth with the vivid present is what I consider exemplary in his approach to China. Moreover, he recognized the importance of collecting and accessing sources for further research. That’s tedious work, and it doesn’t earn one great accolades, but it lays a foundation that potentially generations of researchers can build upon.”

(Source: Written interview of the authors with Dr. Hans-Wilm Schütte, September 15th, 2023)