Passage to China

Through the Three Gorges, 1911

Along the Anning and Yalong Rivers, 1910

Journey to Liangshan – in the land of the Yi, 1913

Departure – Yunnanfu towards Suifu, 1917

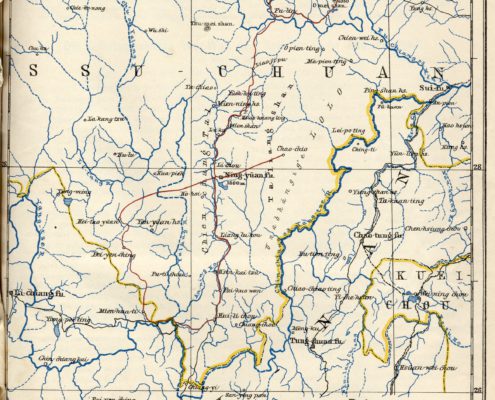

Source: Bacons Large Excelsior Atlas of the World, map: Asia and Europe (selection), London: Bacon, ca. 1920. Shelfmark of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: IIIC 2° Kart. B 1858.

1 Passage to China

Fritz Weiss took numerous photographs on his passage to China, of which only a few can be accurately dated. Here are some recollections of his first passage to China in Autumn/Winter 1899 from Marseille towards Port Said (Egypt), through the Suez Canal to Aden (Yemen), Colombo (Ceylon), Penang (Malaya), Singapore, and Hong Kong with the destination in Shanghai.

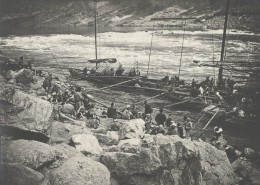

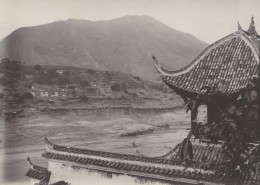

2 Through the Three Gorges – from Shanghai towards Chongqing on the Yangzi, 1911

Fritz and Hedwig Weiss arrived in Shanghai at a time when unrest – the harbinger of the 1911 revolution – was being reported in Sichuan. Despite the danger, after a short stay in Shanghai, they first made their way towards Chongqing, and then further towards Chengdu, the seat of the consulate in which Fritz was employed. The only way to inland Sichuan was at that time with a ship on the Yangzi. In autumn and winter, the water-level was too low, so they were unable to take a steamboat, and had to travel by traditional houseboat, whose crew had to row, sail or haul, according to the situation.

Sound recordings of the songs of the Yangzi Trackers

Edison Phonograph

The Phonograph made it possible to record and reproduce sound. The sound, bundled through a funnel, induces a membrane to vibrate. A needle attached to the membrane engraves the movement of the sound onto a wax cylinder which is rotated during the process of recording.

Edison Home Phonograph and a selection of cylinders

Ident No.: MV 686 e 16/3, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum.

Photographer: Martin Franken

Fritz and Hedwig Weiss did not only bring cameras for the documentation of their travel impressions, including a plate camera which captured the photos on glass plates, but also an Edison phonograph for the recording of sound documents on wax cylinders. These recordings are in the possession of the Berlin Phonogram Archive of the Ethnologisches Museum. In China they recorded the songs of the Yangzi trackers as well as the Yi minority. The Yangzi trackers were coolies, who brought the cumbersome junks through the rapids on the Yangzi, between Yichang and Chongqing, as well as upstream from Chongqing, and on the tributaries. According to the situation, they had to sail, row or haul, this meant pulling the ship through the rapids on long ropes, from the river bank. They had numerous songs to accompany their work:

“Passing the rapids (side rudder)” (Weiss West China, cylinder 2)

This song was sung during downstream rowing. It reflects the situation in overcoming the rapids.

“Calling (luring) the wind, hoisting the sails” (Weiss West China, cylinder 4)

“During a lull, when one needed to get rowing, whistling was meant to lure the wind. As soon as the wind came up, the sails were hoisted. Partly a tremolo was produced by beating with the hand on one’s mouth.”

Recorded in Sichuan, 1912. The information about the content of the songs are historical information that are attached to the recordings.

Source: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin Phonogram Archive. Collection Weiss China.

3 Along the Anning and Yalong Rivers, 31 July to 30 October 1910

Fritz Weiss’ travel route at the Chienchang Valley, 1910

Source: Petermanns Geogr. Mitteilungen, 1914, I, plate 39

In the late summer of 1910, Fritz Weiss made a trip to the extreme southwest of the province Sichuan. His journey took him from Chengdu along the Min River to Jiating, along the Anning River (Chien-Chang Valley), until the border of Yunnan, where the Yangzi and Yalong flowed together.

“The Foreign Office received my proposal, to undertake an extensive journey to the southern end of my province, to make myself acquainted with the economic situation there. […] Quite off my own bat, however, I had the bold idea of undertaking an incursion into the mysterious land of the Lolo.”

“I should start by saying that I had made my plans without consulting my host, Chao Erh Feng [Zhao Erfeng 趙爾豐, 1845-1911], who was well disposed towards me. He had apparently heard something of what I intended – what can ever remain secret in China? – and sent strict telegraphic instructions that all the authorities along my route should in every way hinder any attempt of mine to leave safe, well-trodden paths. Such are the unavoidable disadvantages when you travel as an official in the Chinese interior, since the provincial governors feel they have a responsibility for your life. […] and now, of all things, I want to travel to the land that the Chinese contemptuously regard as barbarian and inhabited by dangerous mountain dwellers.”

(Fritz Weiss, Memoirs, 1946, transl.)

Chienchang Valley

The Chienchang valley (Jianchang 建昌) refers to the river basin of the Anning River between Lugu (瀘沽) in the North, where the two large sources of the Anning River converge, and the area slightly north of the confluence of the Anning River and the Yalong River in the South. Jianchang is an old name of the city Xichang (西昌), which was known in early 20th century as Ningyuan (寧遠). According to Fritz Weiss, the designation “Chienchang Valley” was a term invented by western geographers, not commonly used in China.

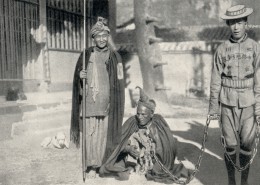

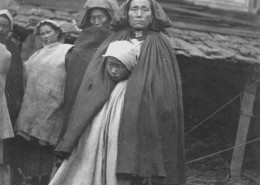

4 Journey to Liangshan – in the land of the Yi (Lolos), Autumn 1913

Through the “unhappy experience with the resistance of the Chinese authorities” during his journey in late summer 1910 along the Anning and Yanlong rivers, with the goal of a detour to the land of the Yi people, Fritz Weiss had learnt, as he himself wrote in his memoirs, “to be more reserved about disclosing my travel destinations in future.” As a result of the “chaotic state in the province” and the “utmost secrecy of my plans by us and our people”, Fritz and Hedwig Weiss succeeded in making an expedition to the mysterious land of the “Lolos”, the Yi people, in November 1913, in the second year of the Republic. “By the time the local authorities finally noticed what was going on, we were already out of their sphere of influence and miles away.” (Fritz Weiss, Memoirs, 1946, transl.) From this short journey to Liangshan in November 1913, from Ebian (峨邊, O Pien Ting) to Mabian (马邊, Ma Pien Ting) particularly portraits and group photos are available. The goal of this journey was especially to quell Fritz and Hedwig Weiss’ curiosity of the unknown people of the “Lolos”.

The Yi people

The Yi people

The Yi people (彝) are native to Southwest China, including the provinces Sichuan and Yunnan. Traditionally, the society of the Yi was ruled by local chieftains (Tusi 土司), who administered several clans. Furthermore, the society was separated into hierarchical classes. The Tusi were part of the Black Yi (Nuohuo), the class of ruling aristocrats. The White Yi (Qunuo, Quho) were vassals and subjects of the Black Yi; they were in command of their own subordinates’ labour and, to some extent, owned property. Other classes included serfs of the black and white Yi, who, in varying extends, had the right to obtain their own property through farming and trade.

At the time Fritz and Hedwig Weiss were in China, “Lolo” was a derogatory designation of the Yi. In this exhibition, the usage of the term “Lolo” is retained in the quotations, to maintain the original character of the diaries.

Hedwig Weiss on the societal system of the “Lolos”:

“There are chieftains, aristocrats and bondmen. Each clan is ruled by a chieftain, whose sovereignty is hereditary, and often it is bequeathed to the bravest and strongest of the sons. There are also aristocrats, who only have command over villages. The aristocrats call themselves Black Bones [Heigutou 黑骨頭], to differentiate themselves from the vassals or the bondsmen. These mainly are [descendants of] captives of war and no longer as pure blood Lolos as Black Bones are. For centuries their blood has been mixed with Chinese who were stolen and put into slavery. The more generations a vassal has, the higher he climbs in social hierarchy of the Lolos. Even when the daily way of life, housing and clothing of the aristocrats hardly differ from those of the bondsmen, there continues to be a deep social divide between them.”

(Hedwig Weiss-Sonnenburg. “Von O Pien Ting nach Ma Pien Ting durchs Lololand”. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin (1915), 73-91, transl.)

Songs and Singing of the Yi

“In the afternoon we attempted to record a few Lolo voices on the phonograph. […] late in the evening, when we were just about to lay down and sleep, a messenger came to the tent and asked us to appear once more, the wife of the chief would like very much to hear the wonderful singing and speaking machine once again. […] A young bondsman with a lovely and clear voice sang. His repertoire exceeded all of our expectations. Lullabies, battle songs, shepherd’s songs and songs sung at weddings and feasts. And after the successful recording, when we put on the reproductor and repeated the successful song, all the faces shined and such hearty laughter sounded, the likes of which I have never heard from the Chinese. […] When the battle song sounded, the black eyes of the Lolo sparkled and they called and screamed along. One would never wish to approach them as an enemy.

For us it was as if we had a look into the soul of this extraordinary tribe. Songs sung by the people, is that not an expression of their soul? We see them on the open pastures, how they briskly jump over cliffs and gorges with their flocks, we see them in the dark shadows of the primeval forests, and the oppressively humid nature has also imprinted itself on their forest songs, which they sing while searching for twigs and roots. We see them in constant battle with the goat-stealing panthers and the maize-stealing bears, their melodies now sound fierce and distressed at the same time. We see them in battle, man against man, whose nerves are tautened to the extreme, wild like animals, whose cries sound jubilant and cheering. Yet tender feelings also live in the same battle-ready chest. Is there anything more lovely than the tender farewell song of the old sister to the younger, with the drawn-out, melancholic sound, or the gentle lullaby?”

(Hedwig Weiss-Sonnenburg. “Von O Pien Ting nach Ma Pien Ting durchs Lololand”. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin (1915), 73-91, transl.)

“Song sung when picking roots” (Weiss South China, cylinder 1)

“The singer complains about the thief who took off with the roots he picked and instead put stones in his basket.”

“War cries during battle” (Weiss South China, cylinder 5)

The text reads: “Two at a stroke, bash, prick, shoot him down. “Dum” – the sound of a gunshot.”

“Shepherds” (Weiss South China, cylinder 7)

“The shepherd tells the goat how life is on the Daliangshan, the freshness of the grass, the clear water etc. …” The song is intended to drive the goats.

Recorded at the Wu Pao Chia clan in Sichuan, November 1913. The information about the content of the songs are historical information that are attached to the recordings.

Source: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin Phonogram Archive. Collection Weiss China.

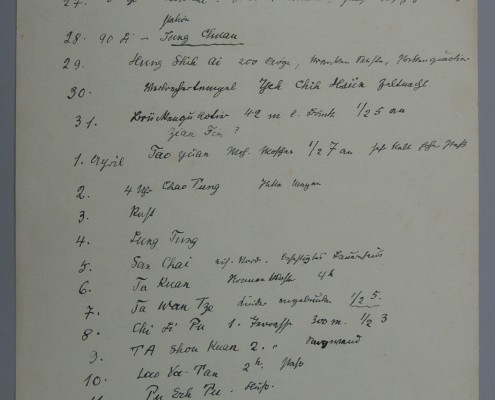

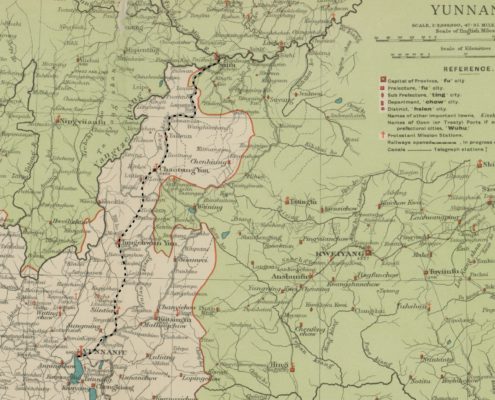

5 Departure over land from Yunnan-fu (Kunming) towards Suifu at the Yangzi, 21 March to 19 April 1917

Travel Route of the Family Weiss, 21 March until 26 April 1917

Map source: Complete Atlas of China (2nd ed.), map: Yunnan, p.16. Specially prepared by Edward Stanford for the China Inland Mission, London: Morgan & Scott [1909]. Shelfmark of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: IIIC 4° Kart. E 934<2>. Selection with marked travel route.

With the start of China’s involvement in the First World War in the autumn of 1917, diplomatic ties with Germany were severed. The Weisses had to leave China, and for that they had to make their way from the interior of China towards Shanghai on the coast. Hedwig Weiss wrote about this in a travel report:

“One day, the time had come, and after a lengthy period of trepidation, after days filled with fear and doubt, we received the final, certain message from Peking: ‘Ties with China broken off.'”

“Now, the overland journey that had been long in the planning had truly come upon us, and it was causing us great worry. Certainly we had taken such a journey in inland China before, but now we had two young children of the ages nine months and two years. More than three thousand kilometres separated us from Shanghai, the journey thither, across China would take six to seven weeks!”

“Eight days – at first it was said to be 48 hours – we were given to make preparations for our travel. We attempted to pack away our possessions and furnishings as far as possible; for we could only take the most necessary clothes and provisions on the arduous overland journey. On 21 March it was all settled, and the journey began.”

(Hedwig Weiss-Sonnenburg. “Dreitausend Kilometer quer durch China. Erinnerungen einer Deutschen aus dem Jahr 1917”. Nord und Süd, Jg. 44 (November 1919), 173-184, transl.)