Walking the streets of the People’s Republic of China [PRC] in the 1980’s they were a common sight: Small stalls along the roadside, often fixed to cargo bikes or carts, that offered picture books for children and grown-ups alike to read on the spot for a small fee.

The term lianhuanhua 连环画 (a direct translation would be consecutive images) was used in China since the 1920’s, it became a fixed term after 1949. Lianhuanhua have their own tradition that goes back to book illustrations of the 14th century. Although there have been influences of western comics they were rather an enrichment than a replacement of the original elements.

The format of lianhuanhua did not see any noticeable changes from the 1950’s to the 1980’s. During the Cultural Revolution production collapsed nearly completely and even several years afterwards, only new editions of popular and politically harmless stories were published. In the 1980’s lianhuanhua sank into insignificance, since then, they have only been popular as collector’s items.

The collection

The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin acquired the lianhuanhua from the PRC in the 80’s. Almost 400 titles from the 1950’s – with a focus on 1956 and 1957- allow an insight into the first ten years of the People’s Republic. Due to copyright regulations, digitization has not been possible so far.

Number

about 400 titles

Shelf marks

5 A 256236 – 5 A 256645

Search

Stabikat

Short history of lianhuanhua in China

Development from the 14th century

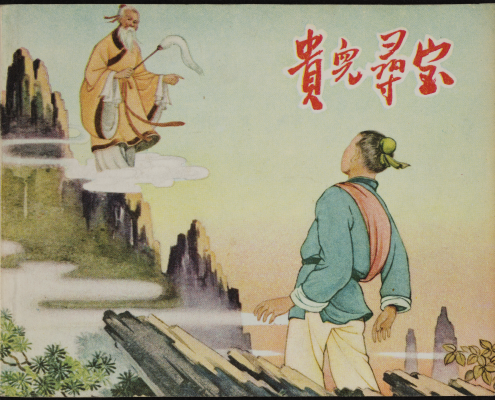

Lianhuanhua were used as a medium of entertainment and education long before the founding of the PRC. Picture series with accompanying texts from the 14th century with stories spreading Confucian morals or to further religious education are considered to be their forerunners. In the 1920’s, stories with various topics, first printed on a single sheet, later assembled to booklets or printed as continuation stories in newspapers came into being. In the 1930’s comic books from western countries emerged in China. Local adaptations and successor products were popular and spread quickly. The emergence of lianhuanhua in Shanghai was favoured by western influences and the existence of a working or middle class readership. Shanghai became the main place of production.

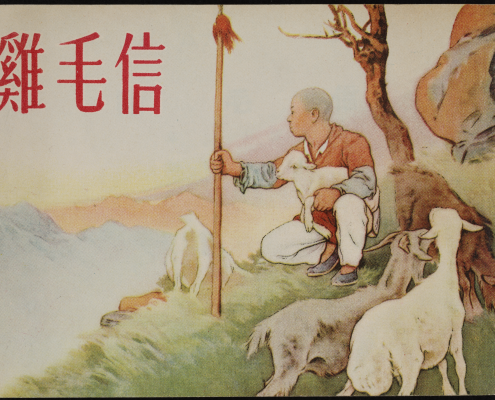

Politicisation during the Republic Era

The politicisation of Chinese society in the 1930’s and 1940’s brought along a wider range of topics. Patriotic and revolutionary stories joined ghost and sword fighting stories popular at the time. The possibility of using lianhuanhua as a medium for spreading political awareness was discovered by intellectuals and implemented by some young illustrators. Until the 1950’s lianhuanhua with political stories remained the exception. The most popular stories, besides stories about ghosts and sword fighting, were adaptions of folk literature and local operas. Their drawing style relies on the traditions of book illustrations and woodblock printing.

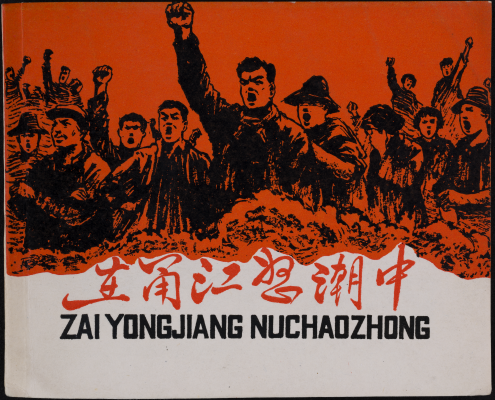

Lianhuanhua as a means of education and propaganda in the PR China

Since the 1950’s lianhuanhua spread knowledge and political messages with the aim of “educating the masses”. The vast majority of the population was illiterate. This changed during the 1950’s through intense literacy campaigns.

Distribution

With the establishment of state controlled publishing a large output of progressive, e.g. politically acceptable, stories quickly outnumbered the ghost and sword stories of privately owned publishers. In parallel, more and stricter controls targeted the traditional distribution channels of privately owned publishers, i.e. small stalls along the roadside where lianhuanhua could be read on the spot for a small fee. Exchanging unwelcome lianhuanhua for politically correct ones or even destroying inappropriate titles belonged to the measures taken. The creation of the state-owned bookstore chain Xinhua Shudian enabled easy access to progressive lianhuanhua within the PRC. The aim was to spread political messages and propagate a socialist role model, thus helping to establish and consolidate the socialist system.

Displacement

Publishers acknowledged the importance of entertaining aspects in order to increase the acceptability of the political messages. By 1960, private publishing companies could no longer compete with the higher quality of the drawings, print etc. of politically favored stories. The concept of lianhuanhua gaizao 连环画改造 further increased the acceptance of progressive lianhuanhua by utilizing the “old” for the “new”, e.g. using forms and features of established lianhuanhua.

Education

Lianhuanhua were a mass product, well suited for the education of the population. They propagated campaigns like “The extermination of the four plagues”, promoted the new socialist family policy, criticized practices of the “old society” and encouraged the construction of a socialist society by the tireless efforts of individuals.

Form and Style

Form

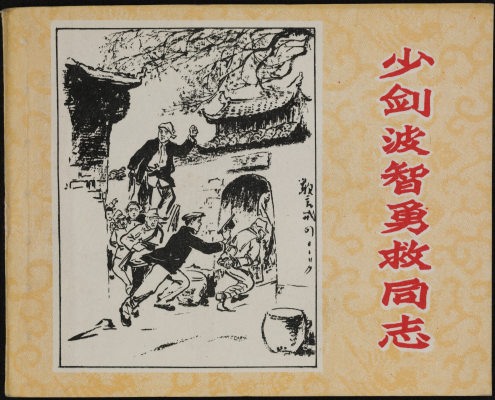

Following short introductory matter, short text segments usually occur in the outer or lower margins of each page. Due to the small size (between 10 x 12 cm and 12 x 15 cm landscape format), each page holds a single picture frame. Speech bubbles are mostly absent, or used sparingly. The form of lianhuanhua remains stable throughout the decades.

Language

The script reform of 1955 found its way to lianhuanhua texts only hesitantly, a mixture of traditional characters and widely used abbreviations remains dominant throughout the 1950’s.

Production

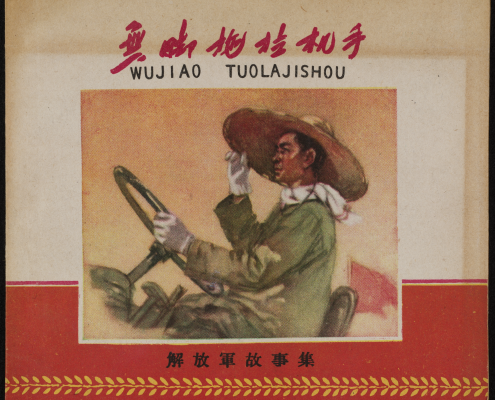

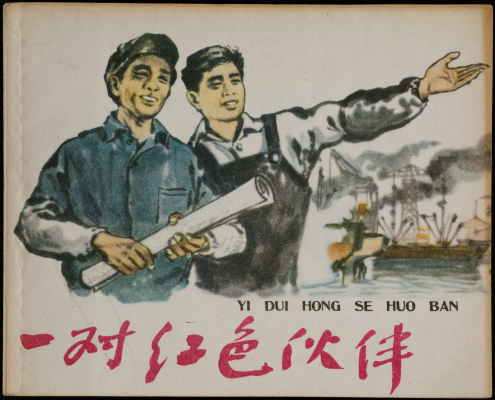

Paper and printing of many lianhuanhua are of poor quality, mostly in black and white, with just the covers printed in colour. Important places of lianhuanhua production were Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin and Chengdu.

Style

Western elements, such as perspective drawing, complemented the visual tradition of the 1930’s, a realistic representation became mainstream. In most lianhuanhua the drawings are made with a pen, with hatched areas. Only few were painted by brush. Photographs, instead of drawn pictures, accounted for only a small part of all lianhuanhua.

Martyrs and heroes

There are numerous stories about people who serve as role models through their behaviour and selfless commitment to their country. They live socialist ideals, their presentation in the stories is solely positive. Many of them are victims of the old society, martyrs, heroes and heroines, sacrificing their life for socialism and their fatherland.

War and friendship of peoples

Besides stories about the Korean War and the war against the Japanese invasion, topics like the relationship with national minorities and the friendship with other socialist countries, including adaptations of Russian literature, found their way into lianhuanhua.

Construction of socialism

Education and agriculture are frequent topics, as the need for knowledge transfer was high in both areas. The aim was to present role models, perfect workers and peasants, for the construction of the new society. Demonstrating the progress that had already been achieved and pointing out the problems already overcome.

Film lianhuanhua

A special case are stories that were neither painted nor drawn, but composed of photos gathered from Chinese and Russian films produced in the 1950’s, most of them adaptations of European and Soviet Russian stories.

Literature and opera

Stories from classical and folk literature or opera pieces were produced and sold side-by-side with lianhuanhua with socialist education contents. They were never banned due to their popularity. After 1949, however, mainly stories with patriotic or revolutionary contents that supported the goals of socialist education were printed.

For many readers, multi-volume series of e.g. shuihu zhuan 水浒传 were the first point of contact with classical literature or Chinese history. Because of the simple manufacturing process – adapting already existing stories to a new format – numerous literature adaptations were published. Adaptions of novels written after 1949 occured alongside adaptions of classical literature.