The first Chinese in Germany

Fung Asseng 馮亞星 (1792/3-?) and Fung Ahok 馮亞斈 (1798-1877) and their transcripts of the Luther Bible in Chinese

According to current knowledge at least four libraries in Europe own early transcripts and adaptions of texts of Martin Luther in Chinese, and done by Chinese: The Berlin State Library possesses three, all from the years 1828/1829. They were made by Fung Asseng, the probably first Chinese who ever came to Germany two hundred years ago (Asseng arrived at the end of 1821 in Hamburg). Asseng presented his transcripts to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III., who in turn gave them to the Royal Library Berlin (Königliche Bibliothek zu Berlin). These are translations of The Small Catechism of Martin Luther (Luthers Kleiner Katechismus), from February 8th 1828, and in parts of Luther’s translations of the bible into German, the Gospel of Luke 聖傳福音路加, written down from April 9th till November 4th 1828, and the Gospel of Marc 傳福音馬耳可, written down from November 18th till May 10th 1829. The Bibliothek der Hansestadt Lübeck possesses at least one part of such an early transcript, again Gospel of Marc, interestingly enough from the pen of Fung Ahok, Fung Asseng’s travelling companion. And also the Vatican Library has in their stock such one piece, a part of Ahok’s transcript of Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Die Epistel Sankt Pauli an die Römer). And finally, the Marienbibliothek in Halle possesses manuscripts from the pens of both Asseng and Ahok.

Life

Family backround, childhood and youth in China

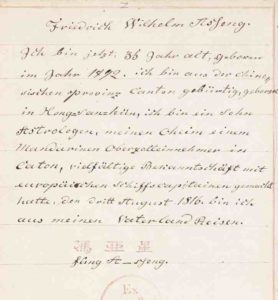

Fung Asseng’s curriculum vitae written by his own hand, in his translation of Luther’s Small Catechism (1828). East Asia Department. License : CC-BY-NC-SA

Fung Asseng (Feng Yaxing 馮亞星, also Feng Yasheng 馮亞生 or Feng Yahao 馮亞浩) was born the son of a priest and astrologer in 1792 in the Southern Chinese province of Guangdong 廣東 . Very likely at the suggestion of his uncle he left China the first time in 1816 to make his luck in the West. His uncle was working as an interpreter in the interpreter agency (tongshiguan 通事舘) in the Thirteen Factories 十三行 of Guangzhou 廣州, a flourishing special district, monopolistically open for foreign merchants. Fung Asseng lost his father at the age of five. His mother cared about his training in written Chinese, so Fung Asseng frequently spent time in his uncles house, and acquired first knowledge of the English language.

Fung Asseng’s way to Berlin

According to his own statements Fung Asseng travelled on a Portuguese ship to Macao on August 3rd 1816, and then went on an English ship to East India and from there to the British island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic. Arround that time numerous Chinese were working on the plantations of the East India Company. Fung Asseng himself probably worked as a cook among the servants of the exiled French emperor Napoleon I. for three and a half years.

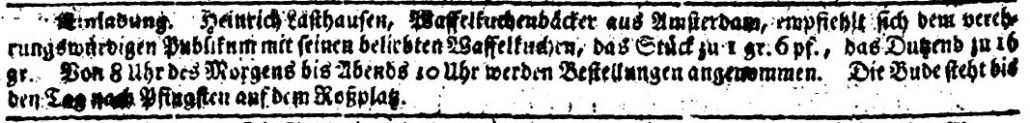

After returning from home leave – not least in order to visit his wife and his two children – he came to St. Helena again shortly after Napoleon’s death in 1821 and travelled from here to London while acting as an interpreter on board between the English captain and the Chinese sailors. In London he met his travelling companion, the 23 years old Fung Ahok (Feng Yaxue 馮亞斈[學]) at the East India House – headquarters of the East India Company. Fung Ahok, like the uncle of Fung Asseng came from Whampoa and was the son of a silk merchant. They signed a contract with Heinrich Lasthausen, waffle baker and showman. According to this contract both of them had to travel to the continent and agreed to be exhibited for money. That is how they came to the German cities of Hannover, Göttingen, Weimar, Jena, Halle, and finally Berlin.

Advertisement of waffle baker Lasthausen from Amsterdam in the Leipziger Zeitung May 21st 1814. Newspaper Department. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

This statement is printed in Johann Karl Bullmann’s Denkwürdigen Zeitperioden der Universität zu Halle (pp. 215/216).

Fung Asseng and Fung Ahok in Berlin

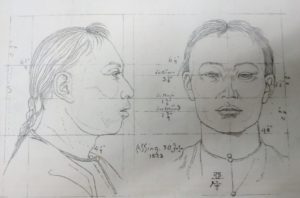

Portrait of Fung Asseng from Schadow’s “Psysionomie nationales” (1835). Department of Early Printed Books. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

In Berlin – as “Der Freimüthige oder Unterhaltungsblatt für gebildete, unbefangene Leser” on March 8th 1823 reports – seven days earlier the two Chinese could be admired at the Behrenstraße Nr. 49, in the very center of the city. Already on January 17th/18th Johann Gottfried Schadow, who was interested in physiognomy, had drawn and measured the two. The original drawings are kept in the National Gallery Berlin today. The portraits were further published as zincographs in Schadow’s Physionomies nationales (1835).

At the University of Halle

Upon the advice of Wilhelm Gesenius King Friedrich Wilhelm III. decided to make them both stay in Germany. He issued a Cabinet ordre on 10th of April 1823 and sent them for lessons in German and Chinese resp. to the University of Halle. After the Grand Elector Friedrich Wilhelm’s plans to create an East India Trading Company and in connection with this his efforts to promote the Chinese studies of Andreas Müller and Christian Mentzel in the 17th century this can be seen as a new attempt to establish Chinese studies in Germany and indirectly to stimulate the development of the trade with China. 4,600 thalers were provided by the Prussian treasury. 1,000 thalers went as replacement sum to carny Heinrich Lasthausen. With the rest of the money two German supervisors as well as living and expences and study costs were financed. Asseng and Ahok such could be released from the contract with Lasthausen. They went to the University of Halle, and were taught here in German by Friedrich Helmke and Wilhelm Schott.

Asseng and Ahok had lessons in German, and Chinese resp. at the University of Halle. New attempts to establish Chinese studies in Germany and indirectly the development of the trade with China. Fung Asseng and Fung Ahok went to the University of Halle and were taught in the German language by Friedrich Helmke und Wilhelm Schott. In turn they were expected to tutor Helmke and Schott in Chinese. In addition they received religious education by superintendent Tiemann; both were baptized on May 12th 1825.

At the Prussian court in Potsdam

They probably stayed in Halle at least until 1825. On a proposal from his Minister of Education and the Arts Karl vom Stein zu Altenstein, the Prussian king on July 8th 1825 decided that both should be educated as gardeners in Potsdam and on November 9th that year Asseng and Ahok were taken as servants into Altenstein’s household. In January 1826 Asseng and Ahok were permitted to marry. On April 2nd 1826 Fung Asseng, baptized as Friedrich Wilhelm Asseng, married Johanne Marie Clara Kraftmüller. Already on February 18th their son Heinrich Wilhelm Asseng was born. Assengs marriage with Johanne Kraftmüller lasted seven years. The couple had four children.

Fung Asseng’s later fate

After the birth of the youngest children on May 3rd 1832, Asseng’s wife passed away. Asseng’s life from now on went bad. In vain he asked for permission to marry the colonist Hallen zu Geltow’s daughter on June 30th 1832. The king did not allow him to marry again, whereupon Asseng fell victim to alcoholism and gambling addiction. In September 1833 Asseng had to serve a three month prison sentence for gambling debts and fraud. He was transferred to the state nursery, made new debts and had to live in Potsdam’s poorhouse. Only his third request for return to China was granted. He was able to return home in November 1836 on a maritime trade ship under the command of captain Johann Karl Rodbertus, before moving to a ship under the British flag in South America. The year of Asseng’s death is not known.

Fung Ahok’s later fate

Feng Ahok’s house in Potsdam, Weinbergstraße 9 (June 2017), license: CC-BY-NC-SA

On January 30th 1826 Fung Ahok received the permission to marry Potsdam’s master carpenter Selle’s foster daughter, probably the very first German-Chinese marriage at all. Ahok was granted an annual salary of 350 thalers, and in addition 30 thalers clothing allowance, firewood, and lodging.

On March 28th 1843 the Prussian King commanded his architect Ludwig Persius to create a private residence for Ahok in Chinese style, and made himself an idea sketch. On July 12th 1843 the king decided to build the house according to Persius‘ plan, and two years later the house was built of exposed yellow bricks, and changed slightly in 1872. Ahok died September 26th 1877 in Potsdam.

Transcripts

Fung Asseng’s Luther transcripts at the Berlin State Library Der kleine Catechismus Lutheri Heiligen Evangelium Lucä Kap. 1-8.28 = 聖傳福音路加 [章 1-8.28] Heiligen Evangelium Lucä Kap. 8.29-17 = 聖傳福音路加 [章 8.29-17] Heiligen Evangelium Lucä Kap. 18-24 = 聖傳福音路加 [章 18-24] Evangelium Marci = 傳福音馬耳可 [cap. 1-8] Evangelium Marci = 傳福音馬耳可 [cap. 9-16] All three translations follow a similar pattern: Below every Chinese character one finds the Cantonese pronunciation in Latin script, and below this the German text.

Fung Ahok’s Luther transcript at the Bibliothek der Hansestadt Lübeck Evangelium S. Marci = 聖馬耳可傳福音書 [II 10., 卷二,cap. 1-16] ::: Bibliothek der Hansestadt Lübeck <1989 A 689> The text is arranged in two columns, the left side consists of the Chinese text, above each Chinese character the Cantonese pronunciation in Latin script, the translation into German is on the right-hand side.

Fung Ahok’s bible transcripts in the Vatican library Die Epistel Sankt Pauli an die Römer = 聖保羅使徒與羅馬輩書 [第一章-第八章] ::: Vatican Library MSS Borg.cin500 The text is arranged in two columns, the left side consists of the Chinese text, above each Chinese character is given the Cantonese pronunciation in Latin script, on the right-hand side is the translation into German.

Descendants

At the end of the 1980s Rainer Schwarz doing research for his article Heinrich Heines „chinesische Prinzessin“ und seine beiden „chinesischen Gelehrten“ sowie deren Bedeutung für die Anfänge der deutschen Sinologie (published in: NOAG 144 (1988) 81-109) got to know Ekkehard Asseng (1937-1993) by fortunate coincidence, a third degree great-grandson of Fung Asseng and had the opportunity to interview him. Ekkehard Asseng was a meteorologist and worked for many years at the Aeronautical Observatory Lindenberg in the field of aerology. In his spare time he made valuable contributions to the preservation of the family history. Jölund Asseng in front of the Neumayer-Station. With kind permission of Jölund Asseng The German Meteorological Society, or to be more exact, it’s secretary Ms. Marion Schnee, arranged contact with his eldest son, Jölund Asseng. To some extent he followed in his father’s footsteps, both professionally as well as in his interest in their exceptional ancestor. Jölund Asseng works as geophysicist at the Alfred-Wegener-Institute of the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, he wintered at the Neumayer-Station in the Antarctic and regularly participates in expeditions there. Brass seal designed by Fung Asseng’s eldest son Heinrich Wilhelm Andreas Asseng, with kind permission of Jölund Asseng. Photo: Christine Kösser, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK. License: CC-BY-NC-SA Like his father he is doing genealogic research, and makes every effort to complete the family tree in Germany, but also in China. Still today in his possession is one last witness for his exceptional ancestor, a brass seal, designed by Fung Asseng’s eldest son, Heinrich Wilhelm Andreas Asseng (1826-?).

Further Sources

Selected literature on the history of the Chinese in Germany: Groeling-Che, Hui-wen von, Dagmar Yü-Dembski (Hrsg.), Migration und Integration der Auslandschinesen in Deutschland, Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 56(2005)2, Wiesbaden: Harassowitz Gütinger, Erich, Die Geschichte der Chinesen in Deutschland: Ein Überblick über die ersten 100 Jahre ab 1822, Münster et. al.: Waxmann 2004 Yü-Dembski, Dagmar, Chinesen in Berlin, Berlin: Berlin edition 2007

Selected literature on Fung Asseng und Fung Ahok:

Hein, Carola, Gunpowder von Ahok, Märkische Allgemeine/Potsdamer Stadtkurier, 04.08.2010, p. 16

Jiang Xueqi, Schriften von und über Fung Asseng und Fung Ahok – Untersuchung zur Phonologie und Transkription von zwei frühkantonesischen Dialekten des frühen 19. Jahrhunderts anhand von deutschen Quellen, Diss., FU Berlin 2022

Oken, Lorenz, Ueber die zwei in Deutschland reisenden Chinesen, Isis 2(1822)11, Litterarischer Anzeiger, Sp. 417ff

Schwarz, Rainer, Heinrich Heines ‘chinesische Prinzessin’ und seine beiden ‘chinesischen Gelehrten’ sowie deren Bedeutung für die Anfänge der deutschen Sinologie, in: NOAG 144(1990) pp. 71-94

Schwarz, Rainer, Noch einmal zu Heinrich Heines “zwey chinesischen Gelehrten”, in: Monumenta Serica 64(2016)1, pp. 173-200