The Origins of the Japanese Collection of the SBB-PK

Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg (1620-1688), the Great Prince-Elector and founder of the library, took already a keen interest in East Asia. Under his patronage, a large number of Chinese books found their way into the Great Prince-Elector’s court library already during the 17th century. However, due to the Japanese isolationism between the 1630s and the enforced opening of the country in 1853 by the American Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858), it was possible to a very limited extent to acquire books from Japan. Until the 19th century, only four Japanese works found their way into the library, of which a mere two are still extant today. The “Flora Japanica” (shelf mark Libri pict. 40, 41) was originally a picture scroll with 1360 representations of plants and birds. In its present state, it is divided into single sheets. It was commissioned in 1685 by Andreas Cleyer (1634-1697), the head of the Dutch East India Company in Japan. The Japanese Honzō kōmoku (本草綱目, shelf mark Libri sin. 102/107) is a Japanese edition of the eminent Chinese compendium about herbs and medicinal drugs, Bencao gangmu. It probably stems from the estate of Christian Mentzel (1622-1701), a botanist and a sinologist who also was the personal physician of the Prince-Elector. The work became part of the library’s collection in 1702. The actual beginnings of the Japanese collection at today’s Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (SBB-PK) therefore coincide much later with the commencement of diplomatic relations between Prussia and Japan. In summer 1860, a Prussian expedition led by Friedrich Albrecht Graf [Count] zu Eulenburg (1815-1881) set off eastward in order to secure treaties of “Amity, Commerce and Navigation” with Japan, China and Siam (today’s Thailand). After pertinacious negotiations, the contract with Japan was signed on January, 24th. A more detailed description of the Prussian expedition can be found in the respective thematic portal.

The collection of premodern Japanese titles of the SBB-PK’s East Asia Department comprises in 2021 nearly 1000 titles. Roughly one hundred of these date back to the Prussian expedition of 1860/61. Two thirds can be attributed to individuals; one third of the books were generally registered under the provenance entries “Prussian Expedition” and, respectively, “Japanese Expedition” in the accession registers. Except for materials from the holdings of the head of the expedition, Friedrich Albrecht Graf zu Eulenburg, the collection contains items from the possessions of three further members of the legation, namely, the attaché Max von Brandt (1835-1920), the geologist Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen (1833-1905), and the doctor of medicine, Robert Lucius Freiherr von Ballhausen (1835-1914). While, after the end of the expedition, these items from the possessions of zu Eulenburg, von Brandt and, von Richthofen found their way into the Royal Library quite soon during the 19th century; von Ballhausen’s collection was purchased from his estate only in 1963.

Numbers

105 titles

103 titles, digitized (as of Dec. 2021)

Shelf Marks

Various “Libri japon.” shelf marks

Ballhausen Collection: 37601 ROA – 37650 ROA

Search

OPAC of the East Asia Department (subject heading: Preußische Expedition / Japanische Expedition / Eulenburg / Brandt / Richthofen / Ballhausen)

Digital collections (search with title or shelf mark)

Printed catalogue

Kraft, Eva (ed.). Japanische Handschriften und traditionelle Drucke aus der Zeit vor 1868 im Besitz der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin. Staatsbibliothek und Staatliche Museen: Kunstbibliothek mit Lipperheidischer Kostümbibliothek, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Museum für Völkerkunde. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1982 (Verzeichnis der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland; XXVII,1)

Shelf mark: OLS Ba OA ja 802-1

Acquisitions

Acquisitions in Japan

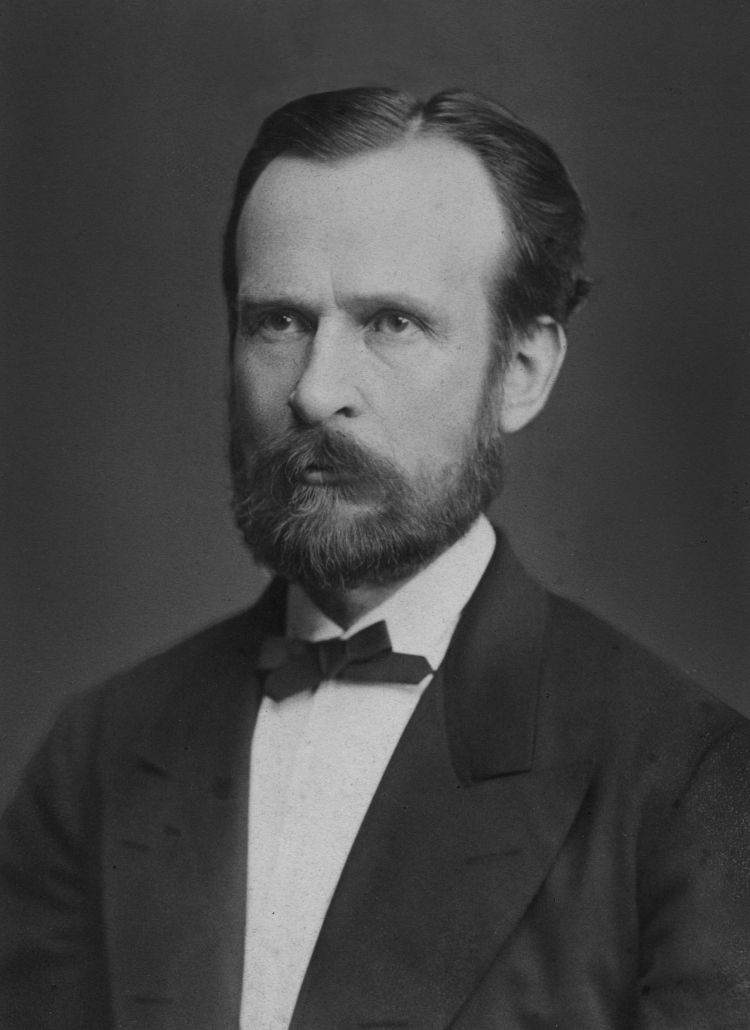

While the departure of the expedition was being prepared, the royal chief librarian, in the rank of a Geheimer Regierungsrat [Privy (Government) Council)], Georg Heinrich Pertz (1795-1873), had his say as well. In a letter dated December 14th, 1859, he asked the minister August von Bethmann-Hollweg (1795-1877) to instruct the members of the expedition that they should, when making their purchases in Japan and Siam, acquire also works for the Royal Library.

Pertz specifically asks for “… historical and geographical works, natural-historical writings containing illustrations, belletristic [schönwissenschaftliche] and vernacular writings, main works of theology and law, hand maps of Japan, Siam and individual parts of the countries, cityscapes and maps…” (Geheimes Staatsarchiv – PK, Berlin, Akte I. HA. Rep. 76 Kultusministerium Vc. Sekt. 1 Tit. XI Teil V A Nr. 2 Bd. 1, p. 207)

Chinese works were not mentioned on this shopping list, which presumably was due to fact that the collection of the Royal Library at the time already contained a substantial number of Chinese titles.

The Royal Academy of Sciences joined company with Pertz and his wishes. In a supplement to a letter addressed to Minister von Bethmann-Hollweg dated February 5th, 1860, we read: “In the interest of the sciences, the Academy wishes that the members of the expedition would take into wise consideration, for the best of the local royal collections, in particular, the Royal Library. 1, in Siam […] 2, in Japan likewise to purchase historical, geographical, natural-historical, ditto theological, poetical, and juridical books, namely, annals of the state and geographical maps.” (Geheimes Staatsarchiv – PK, Berlin, Akte I. HA. Rep. 76 Kultusministerium Vc. Sekt. 1 Tit. XI Teil V A Nr. 2 Bd. 1, p. 244)

The expedition conformed to the request of the Royal Library and spent the amount of 452 Thalers, 3 Silver Groschen and 10 Pfennigs for the purchase of books, maps and manuscripts. However, the final settlement in 1862 evidenced that, in fact, there had never been assigned a proper budget for these purchases in the first place. In order to defray the deficiency, the amount was taken from the “General State Exchequer” and entered in the books of the Royal Library (Geheimes Staatsarchiv – PK, Berlin, Akte I. HA. Rep. 76 Kultusministerium Vc. Sekt. 1 Tit. XI Teil V A Nr. 2 Bd. 2, p. 101-102).

Portrait of the Royal Chief Librarian Georg Heinrich Pertz (about 1870)

Source: bpk / Ernst Milster

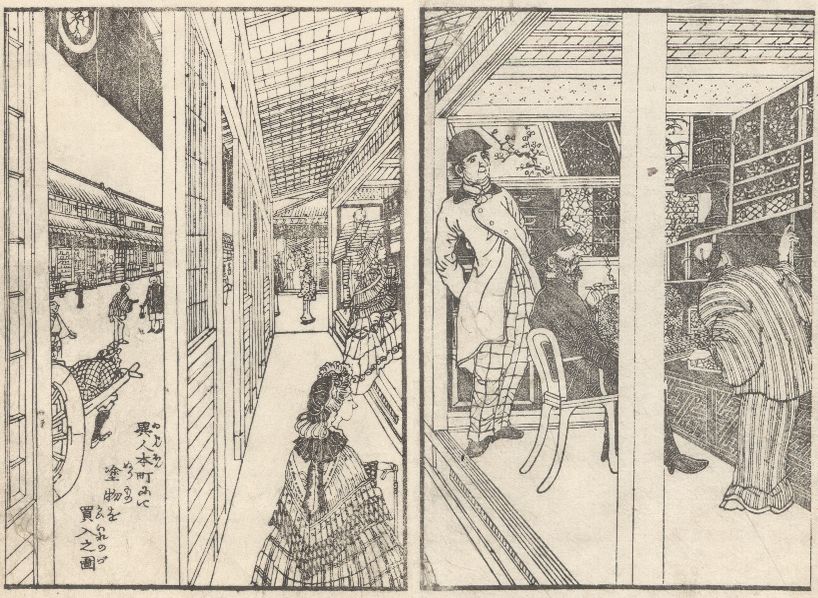

Foreigner at a dealer of lacquer wares in Yokohama

Source: Utagawa Sadahide. Yokohama bunko 横浜文庫., vol. 1, pp. 5v-6r (shelf mark: 39085 ROA)

There was ample opportunity for the members of the expedition to make their purchases in Japan, because between the treaty negotiations, there were long stretches of spare time which needed to be filled with some kind of activities. On the topic of “shopping”, we can read quite a bit in the report contained in the official sources, such as this description of the daily routine in the quarters of the expedition:

“Around eight o’clock in the morning, a large number of hucksters used to assemble, who unpacked from hundreds of boxes and caskets all kinds of cute and useful things. For a couple of hours, the hallway and the passages resembled a motley bazaar, and the objects displayed were so manifold, luring, and inexpensive that everybody’s affinities were satisfied and everybody’s desire to spend was kept alive permanently.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 269-270)

The Prussians were good customers, and Japanese bookstores are mentioned elsewhere in the report:

“In the afternoon, excursions were usually undertaken, and when the weather was too inclement for further horseback forays, visits were paid to bookstores and variety stores, to the weapon-, bronze- and lacquer dealerships nearby, in order to make small purchases, to gain better knowledge of the products of the country and, to converse with the indigenous people.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 270)

Not a trace, however, can be found in the report of the expedition of the wide-spread modern enthusiasm, also in Germany, for Haiku and other Japanese forms of poetry. To the contrary, judgement on Japanese poetry is quite harsh:

“The samples of the poetry that have been translated so far are not very promising. Their poetic perception is for the most part completely impenetrable for our understanding and therefore often seems to be ludicrous and tasteless. Judging by their character, the Japanese are, after all, also not a people gifted with poetical or at least, lyrical, talent, and have most likely never achieved anything remarkable in this field.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 315)

Other branches of Japanese literature, and the Japanese passion for reading, on the other hand, are praised very highly:

“… even the soldiers on guard do read, and one can see children, women and girls, delving into books. Their novels and novellas must be very extensive, and without doubt contain much attractiveness that would merit a translation into European languages. They are rich in history books and encyclopedias; numerous descriptive and educating works from the realms of nature, the sciences, arts and crafts, give evidence of the eager thirst of the people for knowledge.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 314-315)

The eager enthusiasm of the Japanese to read and the reasonable prices of books made a great impression on the chronologist of the journey:

“Reading was the main activity of the Japanese of all classes in their leisure hours; in every street book stores can be found, where not only Japanese and Chinese writings but also translations of European works on geography and regional geography, on medicine, tactics, weaponry, etc. can be found, and the books are so unbelievably inexpensive that one has to assume a very high consumption.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 131)

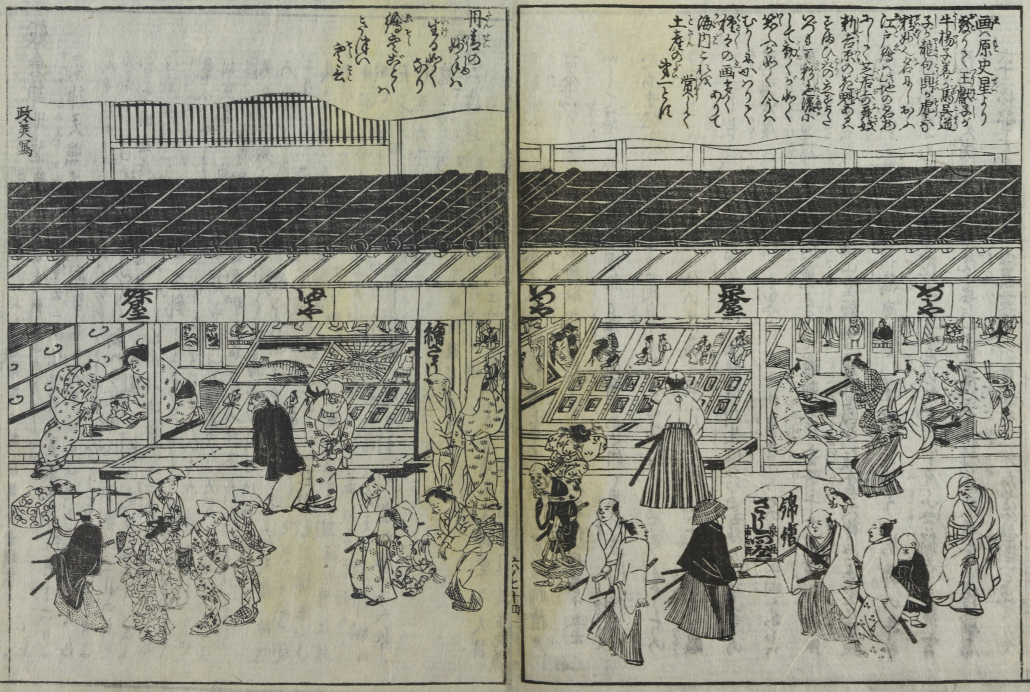

A comprehensive description in the travelogue is appropriately dedicated to book stores and art dealers:

“In front of the book stores and art galleries hang colourful caricatures of a delicious kind of humour, for which the foreigners in Yokohama often have to provide the template. Other than that, one can find landscapes, animals, murder mystery stories and other genres, including beautiful women in magnificent robes and jewellery. The enjoyment of pictorial illustrations is generally widespread, and almost every Japanese seems to be drawing. Already their written language exercises both hand and eye, and since it is a requirement not only to write, but to write beautifully, hence, from early on, a lot of time and diligence is invested into this artistry. The depiction of Chinese written characters with a beautiful swing and proportion is one main condition of Japanese and Chinese education, and in their poems, not just meaning and shape, but also the beautiful flow do have an effect. They demand for the eye what we demand with regard to sound and the sonority of syllables for the ear. They enthuse about calligraphic virtuosity as much as Europeans do about bravura singing and melodious declamation. The training of eye and hand is an essential part of their education and it surely contributes, besides the natural liveliness and comprehension of the Japanese, more than a little to their aptitude for, and enjoyment of, pictorial representations.

A foreign couple galloping on horseback along a shopping street in Yokohama.

Source: Utagawa Sadahide. Yokohama bunko 横浜文庫, vol. 1, pp. 8v-9r (shelf mark: 39085 ROA)

In all book stores, one finds illustrated works in disproportional numbers and hundreds of mere picture books. Most of the botanical and zoological books are illustrated, as are those on physics, anatomy and, tactics — as well as original Japanese books and those translated from the Dutch — moreover, works on weapons, horses, hunting and fishing, gardening and landscaping, tree cultivation, architecture, books on earthquakes, astronomy, meteorology, their calendars of state and genealogies, novels, history books and historical monographs, and their mythological, ethnographical and archaeological works. Their picture books contain now this now that; here, landscape representations, there, scenes of daily life and nature in miniature. We find illustrated alphabet primers, fencing-, riding-, and drawing manuals, where next to the executed sample the basic concept of the shape is represented by mathematical lines. Masterly are their drawings of birds, fish, and insects, of which there are many collections. The majority of picture books contain a multi-coloured mixture of these; often, one can find the most contradictory things wildly thrown together onto one and the same page in a boisterous mood. They are inexhaustible with comical humour. Other volumes seem to have only artistic meaning as facsimile sketch books, with many sheets being excellent, a few of them, however, surpassing in terms of audacity and extravagance anything which has been ever achieved by European schools. All their representations are, in spite of many drawing mistakes, of unbelievable liveliness, showing comprehension and a sense of meaning and characteristics of shapes. Of the sense of beauty and artistically ideal understanding, only a few of their idols and mythological pictures give evidence; nature and daily life are quite possibly closer to the practically minded folk.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, pp. 312-313.)

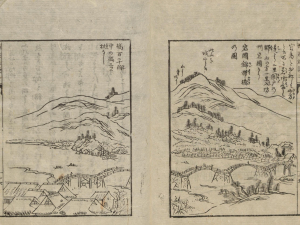

Depiction of the shops of the two publishers Izumiya Ichibee (right) und Masuya (left), both of whom had books as well as Ukiyoe on offer.

Akisato Ritō. Tōkaidō meisho zue 東海道名所図会, vol. 6, pp. 74v-75r (shelf mark: Libri japon. 6)

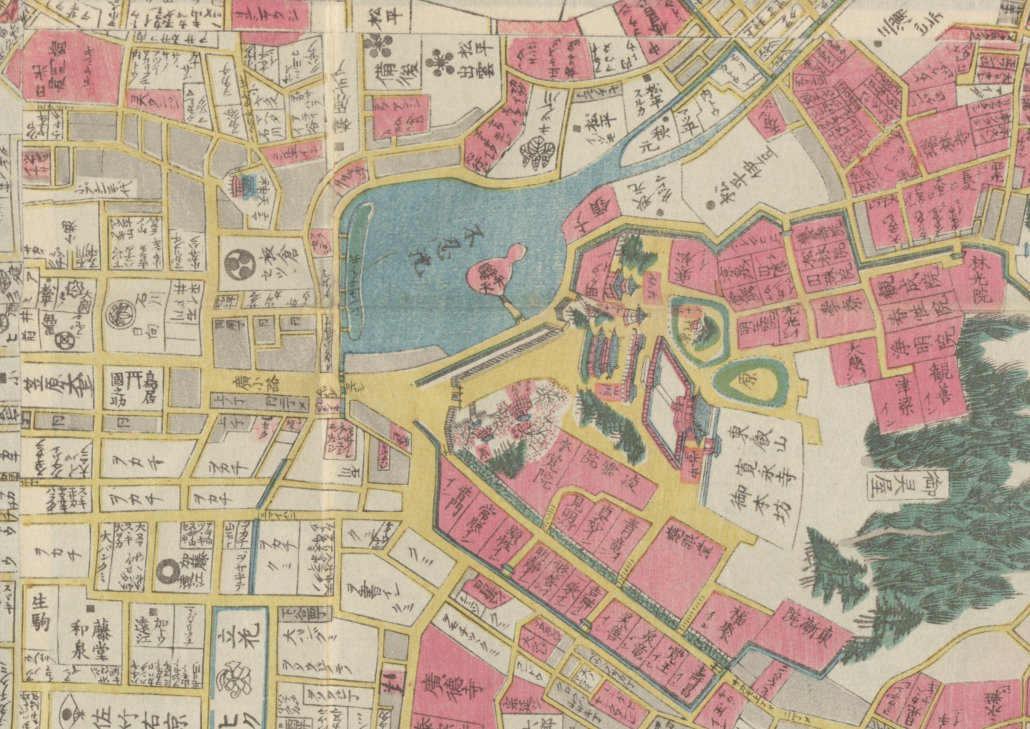

The cartographical works explicitly requested by Pertz, the Royal Chief Librarian, are mentioned in the report and are highly commended for their extraordinary accuracy:

“In all book stores, you can find maps and atlases, partly domestic, containing all parts of the empire, partly reproductions of European works in woodcut or clay print with Japanese script; furthermore, very comprehensive city maps, amongst them one of Yeddo [Edo], four square feet in size, and so clear and exact that we could find all our paths on it.” ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)]. Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 314)

The Japanese collection of the SBB-PK contains a whole range of historical maps, both as reprints and originals. Amongst these is one map of Edo, titled Oedo ōezu (御江戸大絵図, shelf mark: 37619 ROA), from the possession of the medical doctor, Robert Lucius von Ballhausen. With a scale of 1 ft equalling 30 cm, this map with its size of 122,5 cm x 135 cm by all means compares to the city map mentioned above.

City map of Edo (today’s Tōkyō); detail of the Shinobazu pond (in today’s Ueno district) and the island with the Hall of the Benten. The adjacent temple is the Kan’eiji, on the former premises of which today’s National Museum is located.

Source: Oedo ōezu 御江戸大絵図 (shelf mark: 37619 ROA)

Eulenburg

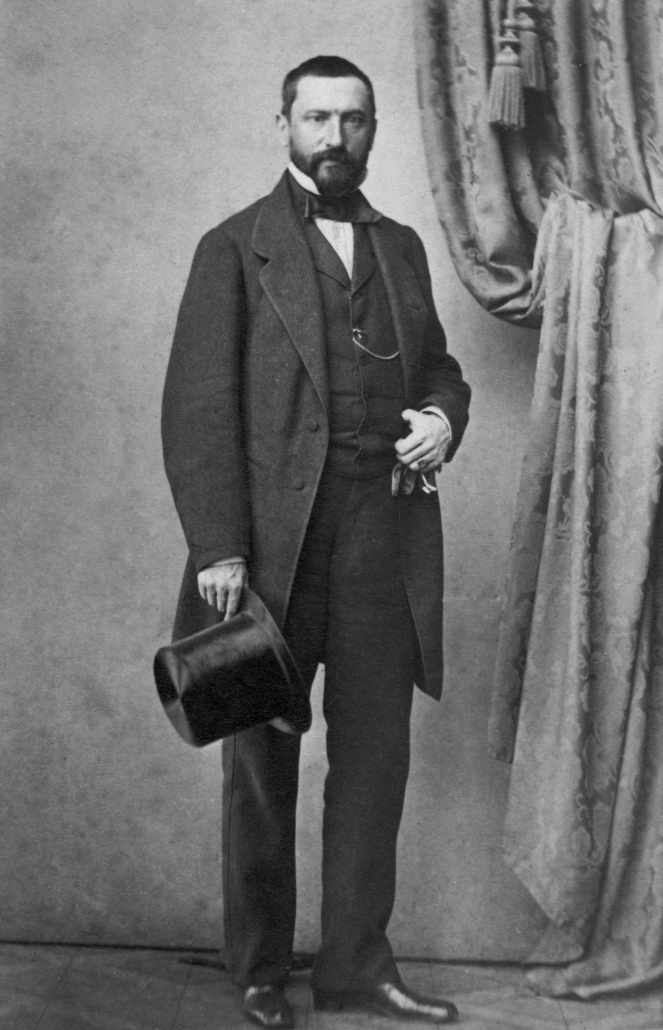

Friedrich Albrecht Graf [Count] zu Eulenburg (1815-1881)

Portrait of Friedrich Graf zu Eulenburg

Source: bpk / P. Biegner Comp.

- Administrative lawyer, diplomat, politician

- Envoy Extraordinary, head of the Prussian expedition to Japan, China, and Siam 1860/1862

- December 1862 – March 1878, minister of the interior in Wilhelm von Bismarck’s cabinet

- The letters von Eulenburg wrote to his family during his travels where published posthumously under the title “East-Asia 1860-1862 in the Letters of Count Fritz zu Eulenburg, Royal Prussian Envoy, entrusted with an Extraordinary Mission to China, Japan and Siam.” (cf. “Selected Bibliography“)

- The files pertaining to the expedition are stored in the Geheimes Staatsarchiv – Preußischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin. An overview of these unpublished sources is given in: Dobson, Sebastian and Sven Saaler (ed.), Unter den Augen des Preußen-Adlers: Lithographien, Zeichnungen und Photographien der Teilnehmer der Eulenburg-Expedition in Japan, 1860-61 = Under eagle eyes : lithographs, drawings & photographs from the Prussian expedition to Japan, 1860-61, pp. 373-374 (cf. “Selected Bibliography“)

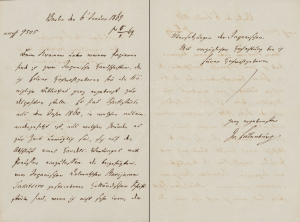

In the collection of the SBB-PK, only one item from the estate of von Eulenburg has survived which found its way into the collection more or less by chance. The shelf mark Libri japon. 446 identifies a bundle consisting of a letter written by the Count, two Japanese letter scrolls and their accompanying Dutch translations. Obviously, von Eulenburg was not keeping his files well organized. Seven years after his return from the expedition, he discovered these documents which were related to his official business in Japan, and he forwarded them to the Royal Library, along with the following letter:

Letter of von Eulenburg to the Royal Library

Source: Monjorui (文書類 (仮題), shelf mark: Libri japon. 446-4)

“Berlin, January 6th, 1869

While rummaging around in my papers, I found two Japanese manuscripts which I herewith enclose and humbly place at the disposal of Your High Well-born for the Royal Library. They consist of documents dating from 1860, concerning the reasons why it is presently impossible to enter into a trade contract with Prussia. The enclosed documents written in Dutch by the interpreter Morijama Takitsiro, are, if I am not mistaken, the translations from the Japanese.

I remain respectfully

Your High Well-born’s most humble

Gr. [Graf, i.e., Count] Eulenburg”

Inscription on the cover of the bundle “Resumé der Conferenz mit den Gouverneuren am 18ten September 1860 in Jeddo” [Summary of the meeting with the governors on the 18th September 1860 in Edo]

Source: Monjorui (文書類 (仮題), shelf mark: Libri japon. 446-3)

As can be inferred from the details provided in the Dutch translation and from what is written on the cover of the bundle, the Japanese letter rolls are related to a meeting of von Eulenburg on September 18th, 1860, (according the the Japanese calendar: 4th day 8th month Man’en 1) with the two commissioners for foreign affairs (gaikoku bugyō), Sakai Oki no kami (= Sakai Tadayuki, 酒井隠岐守 = 酒井忠行, dates unknown) and Hori Oribe no Shō (also: Hori Oribe no kami = Hori Toshihiro, 堀織部正 = 堀利煕, 1818-1860). Four days earlier, on September 14th, 1860 (29th day 7th month Man’en 1), the first encounter had taken place between von Eulenburg and the Japanese chief negotiator, Andō Tsushima no kami (= Andō Nobumasa, 1820-1871, 安藤対馬守 (安藤信正)). During this meeting, von Eulenburg had brought forward the Prussian request to conclude contracts of trade and friendship. This suggestion, however, had been rejected by Andō who pointed out that previous contracts had proven to be very disadvantageous and that, therefore, public opinion had completely turned against conclusion of further contracts. They finally adjourned the point without a result and Andō announced that the commissioners for foreign affairs would in the near future explain the details of the Japanese position once more. This explanation was given just on September 18th, 1860, by Sakai and Hori.

Both in the report of the official sources ([Berg, Albert (Ed.)], Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Nach amtlichen Quellen. Berlin, 1864, vol. 1, p. 293), and in von Eulenburg’s private letter dated September 18th, 1860, it sounds as if only one written document had been handed over on this occasion: “… at two o’clock, received the Governors who had been sent by the Minister, in order to repeat once again all that he had told me himself the other day. In order to really make sure, they have written down everything in Japanese and presented me with a large piece of writing.” (Eulenburg, Philipp zu (Ed.). Ost-Asien 1860 – 1862 in Briefen des Grafen Fritz zu Eulenburg, Königlich Preußischen Gesandten. Berlin, Mittler, 1900, pp. 74-75).

Only in von Eulenburg’s letter to the foreign minister, Alexander von Schleinitz (1807-1885), dated September 19th, 1860 (received Dezember 15th, 1860), it becomes evident that in fact there had been two documents. Von Eulenburg writes: “I did not engage in serious discussions because everything they [the commissioners for foreign affairs] put forward was just a repetition of what I had already heard from the Minister. … What they told me they had memorized from a written instruction which they used as guidelines, and in the end, they presented me with a long Japanese Memoria with a translation into Dutch, in which everything supposedly was expressed even clearer than they had been able to express it verbally.” (Geheimes Staatsarchiv – PK, Akte III. HA MdA, II Nr. 5070, p. 174.)

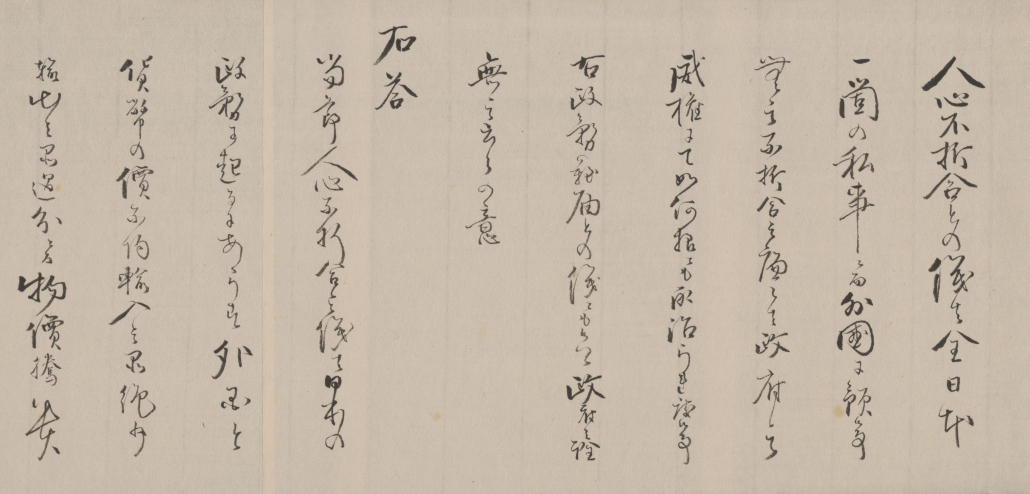

Beginning of the official letter of the “council of elders” (rōjū), i.e., the “Memoria”

Source: Monjorui (文書類 (仮題), shelf mark: Libri japon. 446-1)

Beginning of the “guidelines” of the commissioners for foreign affairs

Source: Monjorui (文書類 (仮題), shelf mark: Libri japon. 446-2)

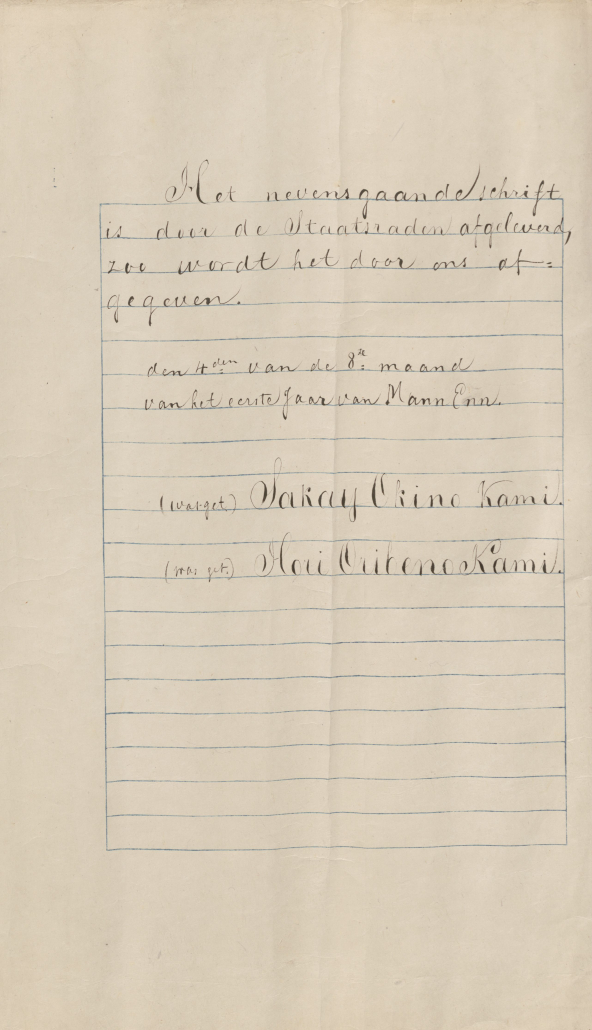

Ending of the Dutch translation by Moriyama Takichirō

Source: Monjorui (文書類 (仮題), shelf mark: Libri japon. 446-3)

Actually, the item with the shelf mark Libri japon. 446-1 is just this Memoria mentioned above, the official document of the “council of elders” (rōjū) sent to the Prussian envoy which is also contained in the published collections of documents:

- 『通信全覧 第6巻』 原本所蔵外務省外交史料館、通信全覧編集委員会編、復刻版、1985年、頁178~180

- 『大日本古文書 幕末外国関係文書 第41巻』 東京大学史料編纂所編、復刻版、1987年、頁145~147

- 『幕末維新外交史料集成 第5巻』 維新史学会編、1978年、頁93~94

The item with the shelf mark Libri japon. 446-2, on the other hand, is the “guidelines“, following which the commissioners for foreign affairs faithfully explained once again the three points they were ordered by minister Andō to elaborate on once more. The document itself is not mentioned in any collection of documents and quite likely only preserved on the German side. In the collection of the minutes of the Shogunate government, however, the protocol of the meeting of September 18th, 1860, is contained therein; it terms of contents, it conforms to the “guidelines” (cf.『大日本古文書 幕末外国関係文書付録之八 対話書』 東京大学史料編纂所編、2010年、頁416~424). We can find the text of the Japanese “guidelines” (Libri japon. 446-2) in printed form prepared by Kitamura Hiroshi (East Asia Department, SBB-PK) here.

For both Japanese documents there also exist the Dutch translations (Libri japon 446-3) by the then interpreter Moriyama Takichirō. They can be found in their print reproduction here.

Other Members

Other members of the Expedition and items from their possession >> Please choose from the menu below.

Portrait of Max von Brandt (wood engraving of 1873)

Source: bpk

Max von Brandt (1835-1920)

- Diplomat and author

- Accompanied the Prussian expedition 1860/62 as attaché

- From 1862, consul in Japan; from 1867, Prussian representative in Japan; from 1868, representative and consul general of the Norddeutscher Bund [North German Confederation]; from 1872, consul general of the German empire in Japan

- 1875-1893 imperial envoy for China

- Numerous publications on East Asia, including his three-volume memoirs with the title “Dreiunddreissig Jahre in Ost-Asien. Erinnerungen eines deutschen Diplomaten” [Thirty-three Years in East Asia. Memoirs of a German diplomat] (cf. “Selected Bibliography”)

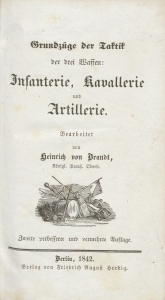

During a breakfast following the meeting of the envoy with the two commissioners for foreign affairs, Sakai Oki no kami and Hori Oribe no shō, on October 15th, 1860, the name of Attaché Max von Brandt came up during the conversation. Sakai and Hori immediately inquired whether this person might be related to the author of a book on tactics that was quite famous in Japan, and they were delighted to hear that Max von Brandt was, indeed, the son of this author. The work in question, written by Heinrich von Brandt (1789-18568), was titled “Die Grundzüge der Taktik der drei Waffen. Infanterie, Kavallerie und Artillerie” [Fundamentals of the tactics of the three weapons: Infantry, cavalry, artillery], published originally in 1833. It had been translated into the Dutch language and then, from the Dutch into — even two — Japanese versions. One of these Japanese editions, Sanpei kappō (三兵活法) was prepared by Suzuki Shunsan (i.e., Suzuki Tsuyoshi) in 1846 (Kōka 2). The other edition was published only a little later during the early Ansei-period (1854-1860) and was produced by Takano Chōei under the title Sanpei takuchiki (三兵答古知幾).

Title page of “Die Grundzüge der Taktik der drei Waffen. Infanterie, Kavallerie und Artillerie” (Berlin: Herbig, 1842, 2. verb. u. verm. Aufl.)

Source: shelf mark: Hv 597-6,1a

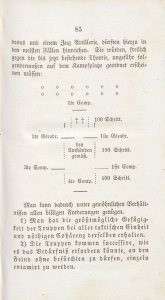

Schematic representation of a combat formation with different military units in “Die Grundzüge der Taktik der drei Waffen. Infanterie, Kavallerie und Artillerie”

Source: shelf mark: Hv 597-6,1a, p. 85

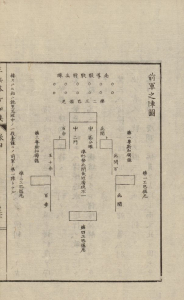

The same schematic representation in the Japanese translation Sanpei takuchiki

Source: shelf mark: Libri japon. 14, Heft 4, p. 21r

Sales cover with the inscription “Dem Verfasser zugesandt durch den Gouverneur des Auswärtigen, Fürst Hori Oribe no kami” [Sent to the author by the Governor of the Exterior, Prince Hori Oribe no kami]

Source: Brandt, Heinrich von. Sanpei takuchiki 三兵答古知幾, Edo, 1857, sales cover of vols. 9-12 (shelf mark: Libri japon. 14)

On December 4th, 1860, Hori presented Max von Brandt with a Japanese edition of the book. This present has survived the many years that went by since the wxpedition. It is now part of the collection of the SBB-PK. This copy is one of the later Japanese translations with the title Sanpei takuchiki. This is substantiated by the dedication on one of the sales covers “Dem Verfasser zugesandt durch den Gouverneur des Auswärtigen, Fürst Hori Oribe no kami” [Sent to the author by the governor of the exterior, Prince Hori Oribe no kami] (shelf mark Libri japon. 14, sales cover of vols. 9-12). Another sales cover is also showing the name “Heri [sic] Oribe no kami” (shelf mark Libri japon. 14, sales cover of vols. 13-16).

Sales cover with the name “Heri [sic] Oribe no kami”

Source: Brandt, Heinrich von. Sanpei takuchiki 三兵答古知幾, Edo, 1857, sales cover of vols. 13-16 (shelf mark: Libri japon. 14)

Besides that, there exist from the ownership of Max von Brandt a map (8° Kart E 3404), two printed works (Libri japon. 325, Libri japon. 118), one manuscript (Libri japon. 468) and four titles in the form of picture scrolls which are amongst the most beautiful pieces of the historical Japanese collection. This type of illustrated scroll is usually called Nara emaki, (Nara picture scrolls), however, the place name “Nara” is not meant to be understood verbatim, since the artists engaged in these works were not neccessarily all active in Nara.

Gangōji engi (元興寺縁起)

Kanbun era (1661-1673), Nara emaki, Libri japon. 484

The legend that is being told in words and with five pictures in this scroll, which is eleven meters long, is composed of two parts. Even though the contents of both of these parts has also been handed down in other texts, it is the combination of both of them which we find here which is unique.

In the first half, the origin of the Asuka- oder Gangōji-Temple is depicted: the aristocrat Soga no Umako, a follower of Buddhism, founded the Gangōji Temple, whereupon Shima, the daughter of another nobleman, Shiba Tatsuto, and her maidservants decide to become nuns. In the first illustration, Shima and her maidservants have their heads shaved as a symbol of their new status as nuns.

When a disease from China breaks out, the blame for it is laid on the introduction of Buddhism which has also been adopted from China. Its opponents, Mononobe no Moriya and Nakatomi no Katsumi, thereupon have the Gangōji razed to the ground. The second picture shows how the robes are torn off the monks and nuns, a statue of the Buddha and Sutras are burned, and people are about to tear down the temple building.

The disease, however, cannot be contained by these measures und the people are suffering great distress. The Prince and Regent, Shōtoku Taishi, together with Soga no Umako, destroys the clan of Mononobe no Moriya. Shōtoku Taishi establishes the temple Tennōji, and Soga no Umako has the Gangōji reconstructed. Consequently, the situation is pacified and Buddhism continues to spread.

Detail from the first illustration of the Gangōji engi, Shima and her maidservants have their heads shaved and become nuns.

Source: shelf mark: Libri japon. 484

Appearance of the God of Thunder in the third illustration of the Gangōji engi

Source: shelf mark: Libri japon. 484

Next, however, the Gangōji ist being haunted by a devil, which marks the beginning of the second half of the legend. The devil is taken to be a vengeful spirit for the annihilated Mononobe no Moriya clan.

In Owari province, there lived a poor married couple of peasants. Once, while they were working in the fields, a thunderstorm suddenly came up and the God of Thunder appeared amidst a black cloud. The couple thereupon lost conscience, the woman got pregnant and delivered a son, who was endowed with colossal strength. On the third picture, the Thunder God’s appearance is depicted. When the son, Tatsunosuke, turns 16, he confronts the devil and expects him at the temple bell, the sound of which attracts the devil. During the fight, the devil realizes the tremendous strength of Tatsunosuke and tries to flee. Tatsunosuke however grabs and holds him. Picture four shows the scene in the bell tower of the temple, in which Tatsunosuke grabs the devil by his beard and holds him.

At the stone stupa that marks the Mononobe no Moriya clan’s grave, the devil finally dies. The fifth illustration shows his corpse next to the stone stupa. Thus, the Gangōji was purged from the devil and flourished again. Tatsunosuke became a Buddhist monk and took the name Dōjō. This is the origin of the phrase “the Gagoze [Gangōji] is coming”, which is used in order to reprimand children to behave. (The description given above is based on Berurin tōyō bijutsukan, pp. 253-255; cf. “Selected Bibliography“)

The other picture scrolls are the Ennogyōja (えんの行者, Kanbun period [1661-1673], Libri japon. 482), a legend of the founder of the Buddhist Shugendō sect of the mountain ascetics; further, the Mikage no omatsuri (みかげの御祭, Enpō-Genroku period [1673-1704], Libri japon. 457); a depiction of the procession of the Kamo shrine in Kyōto on May 12th (or, according to the lunar calendar, on the day of the Horse in the middle of the fourth month); and finally, the Tsukiō otohime monogatari (月王乙姫物語, Enpō period [1673-1681], Libri japon. 458), a narrative about the Moon-Prince and the daughter of the Ocean- or, Dragon-King. The last one consists of two picture scrolls measuring twelve and fourteen meters, respectively, in length.

“The princess visits the young man in his monastic cell, which leads to his expulsion from the monastery and the banishment from his parental home. In the Ocean Palace, he gets homesick. On his return to earth the princess steals the wishing pearl of the emperor in order to help the humans. It is only when a war between both worlds becomes imminent, that she returns it and moves back with her husband to her parents.” (Eva Kraft, Illustrierte Handschriften und Drucke aus Japan. 12.-19. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1981, p. 42.)

The scene in the Ocean Palace is drawn especially imaginatively. The Ocean’s denizens are represented as bizarre in-between beings with fish, seashells, squids, crabs, and conches on their heads.

Detail from the depiction of the Ocean Palace in the Tsukiō otohime monogatari

Source: Scroll 1, picture 6, shelf mark: Libri japon. 458

In connection with Max von Brandt, two more works are to be mentioned that have, with a detour, found their way into the Royal Library.

- In the case of the Shūko jisshu (集古十種, Libri japon. 337), a picture collection about old Japanese art and culture, the specimen of the SBB-PK came, “according to the testimonial of the Legation’s interpreter on January 6th, 1861, into possession of Max von Brandt, and was later, at the instigation of Mr. Jagor, presented to the Royal Library as a gift by Prof. Dr. Wagner, [who was] attached to the Imperial Japanese Exhibition-Commission in Vienna in 1873.” (Kraft, Eva (Hg.). Japanische Handschriften und traditionelle Drucke aus der Zeit vor 1868 im Besitz der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1982, p. 281).

- According to a letter, the cartographical map series of a land surveying expedition to Hokkaidō, Sachalin, and the Kuril islands, with the title Tōzai ezo ensen chiri torishirabezu (東西蝦夷山川地理取調図, 8° Kart. E 3420) was sent on November 6th, 1865, via Konsul Brandt to the Prussian Ministry of Foreign Affairs where it arrived on May, 21st, 1866.

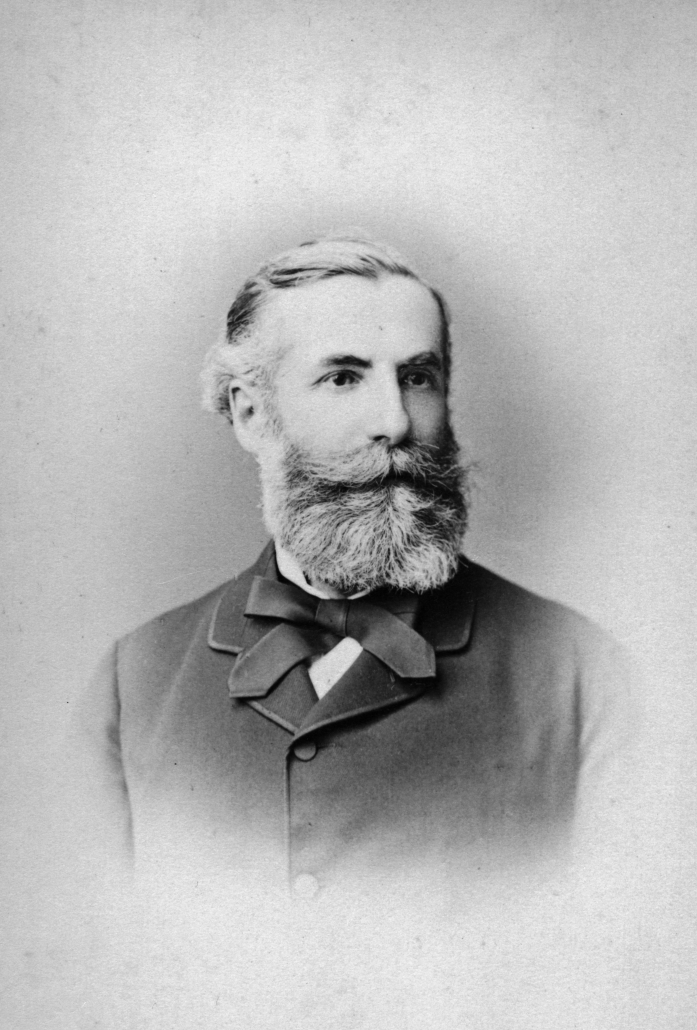

Portrait of Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen around 1880

Source: bpk / Ernst Milster

Ferdinand Freiherr [Baron] von Richthofen (1833-1905)

- Geographer, geologist and explorer

- 1860/62, accompanied in this capacity the Prussian expedition

- 1875, professorship of geography at Bonn University; in 1883, at Leipzig University; in 1886, professorship of physical geography at Bonn University

- 1901, founder and first director of the Institute of Oceanography; building of a Museum of Oceanography (opened in 1906)

- 1903-04, principal of Friedrich-Wilhelm-University, Berlin

- Numerous geological and geographical publications, based especially on his expeditions to California, China, and Japan

Twenty-four pieces date back to the possession of von Richthofen. The works he collected reflect on the one hand his interest in the natural sciences in the form of illustrated works with representations of plants or animals, on the other hand, he also purchased, in accordance with the collection order of the Royal Library, a number of books on different topics, such as drawing patterns or reproductions of artistic works of the Kanō school, several poetry collections and a lexicon of Buddhist iconography.

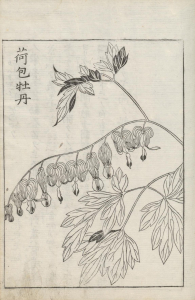

Image of a bleeding heart in Kai

Source: Part on grasses, booklet 4, p. 12r, shelf mark: Libri japon. 432

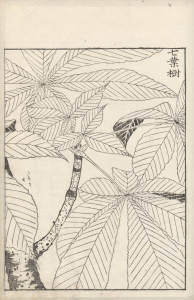

Kai (花彙)

Mid-18th century, 8 booklets, Libri japon. 432

The work Kai consists of two parts with four booklets each, one part on grasses and one part on trees. The authors are Shimada Mitsufusa (島田充房, 1764-1789) and Ono Ranzan (小野蘭山, 1729-1810), with two booklets by Shimada and the remaining six by Ono. The latter one was an eminent botanist and expert in herbal medicine who authored numerous publications. The famous Japan scholar, Philip Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), called him “Japan’s Linné”. Kai contains detailed representations of grasses, flowers and trees, including descriptions. It was the second Japanese botanical work that was translated in its entirety into a European language. The French naval doctor and botanist, Ludovic Savatier (1830-1891) who spent the years 1865 to 1876 in Japan, with the help of a Japanese called Saba produced a French translation that was published, regrettably without illustrations, in 1873 (Livres Kwa-wi ; Botanique japonaise; trad. du japonais avec l’aide de M. Saba par L. Savatier. Paris: Savy, 1873). Moreover, Savatier and the botanist Adrien Franchet (1834-1900) used Kai as one of three Japanese works for their two-volume presentation of the Japanese flora, titled “Enumeratio plantarum in Japonia sponte crescentium…” [Enumeration of the flora growing spontaneously in Japan…]. (Parisiis: Savy, 1875-79).

Image of a Japanese horse-chestnut in Kai

Source: Part on trees, booklet 1, p. 21r, shelf mark: Libri japon. 432

Gakō senran (画巧潜覧)

1740 (Genbun 5), 6 booklets, Libri japon. 94

Compendium of works and painters of the Kanō school, compiled in six booklets by one their disciples, Ōoka Shunboku (大岡春朴, 1680-1763). Their contents are as follows:

- Booklet 1: Lineage of the Kanō school as well as copies of famous paintings with scenes in and around Kyōto

- Booklet 2: Pictures of persons and a copy of a scroll with horses and cranes, originally painted by Kanō Tan’yū (狩野探幽, 1602-1674)

- Booklet 3: Copies of landscape images and paintings of birds and flowers, likewise by Kanō Tan’yū

- Booklet 4: Copies of Tan’yū’s paintings of Japanese and Chinese persons

- Booklet 5: Japanese and Chinese design patterns, remarks on the authenticity of different painters, as well as painters’ signatures

- Booklet 6: Painters’ signatures and seals

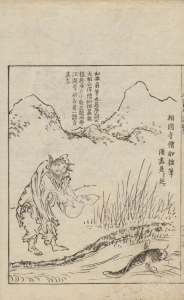

Adjacent: Copy of the representation Hyōnenzu (瓢鮎図, pre-1415), an illustration of the Zen enigma (kōan) about the difficulty to capture a catfish with a bottle gourd. The picture originated with the monk Josetsu (如拙, late 14th – early 15th century) who is considered a pioneer of ink painting in Japan. Today, the picture is classified as ‚national treasure‘ (kokuhō) and located in the Taizōin (退蔵院), a subtemple of the Myōshinji (妙心寺) in Kyōto.

The reproduction of the jumping tiger shows a part of an ink wall painting, that originally was housed in the subtemple Nikkōin (日光院) of the Miidera (三井寺) in Shiga prefecture. It was painted by the eminent member of the Kanō school, Kanō Eitoku (狩野永徳, 1543-1590). During the Meiji period (1868-1912), this painting and other works of art in the temple were acquired by the entrepreneur Hara Rokurō (1842-1933). Nowadays, the painting has been mounted onto a four-part hanging scroll and belongs to the collection of the Hara Museum ARC in Gunma prefecture.

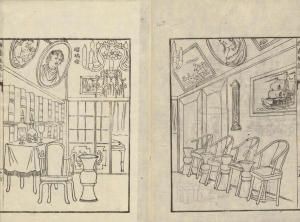

Saiyū ryodan (西遊旅譚)

Revised version, dated 1803 (Kyōwa 3) in 4 booklets, Libri japon. 321

The book was published originally in 1790 (Kansei 2) and, in a revised version, once again in 1803 (Kyōwa 3). Author and illustrator is Shiba Kōkan (司馬江漢, 1747-1818), well-known Japanese painter who besides Japanese painting had also mastered Western style painting with oil paint as well as copper plate printing. Moreover, he studied the Western sciences (rangaku). The work Saiyū ryodan contains the report on his experiences of a yearlong journey from Edo (today’s Tōkyō) to Nagasaki in 1788/89. Booklets 1 and 2 cover the report proper. Booklet 3 describes mainly his observations in Nagasaki, with its numerous foreign inhabitants. The last booklet is dedicated to fishing and whaling. While the landscape sketches are executed in the Japanese manner, Shiba employed a Western style of drawing for schematic representations.

The picture from booklet 2 shows the well-known Kintaikyō bridge (lit.: “brocade sash bridge”) in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi prefecture. This is a wooden arch bridge with a length of 193 meters, built in 1673. Its reconstruction can still be used today.

In booklet 3, the interior of the Dutch captain’s dwelling in Nagasaki is depicted employing a Western central perspective. In the inscription of the illustration, which is mainly missing in the edition at the SBB-PK, the chandeliers, portraits and paintings, the glass items and the chairs are explicitly mentioned. The inscriptions can be found in the original edition of 1790 (Kansei 2) which is in the possession of the National Diet Library Tōkyō (Reprint: 江戸・長崎絵紀行 : 西遊旅譚 / 司馬江漢著. 東京 : 国書刊行会, 1992, p. 125).

Portrait of Robert Lucius Freiherr von Ballhausen (around 1880)

Source: bpk / L. Haase Co.

Robert Lucius Freiherr [Baron] von Ballhausen (1835-1914)

- Medical doctor and politician

- 1860/62, accompanied the Prussian expedition as doctor

- Since 1866, politically active; repeatedly member of parliament; since 1871, close connections to Otto von Bismarck; 1879-1890, Prussian minister of agriculture; 1895, appointment into the “Herrenhaus” [Prussian House of Lords]

- 1888, raised to the rank of Freiherr [Baron]

- 1920, posthumous publication of his “Bismarck Memories”, which constitute, as original testimonies, an important source of information regarding the Bismarck era

In winter 1859/60, Ballhausen who had not yet been ennobled, applied as Dr. Robert Lucius for the position of naval doctor in the expedition. His application, however, was not accepted and so he, for a start, joined the Spanish campaign in Morocco. After this, he made acquaintance with the two attachés, Max von Brandt and Theodor von Bunsen, in Kairo. The two were on their way overland to Singapore where the Prussian expedition was being put together. After he continued to journey on, Ballhausen finally also met with the envoy, Count zu Eulenburg, in Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), and immediately accepted, on the condition that he was willing to waive his wages, zu Eulenburg’s offer to accompany the expedition as a doctor. After the expedition to Japan, China and Siam (today’s Thailand), he continued to travel alone to India and into the Himalayas, before he returned home to Prussia, after an absence of three years. His biography mentions with regard to his stay in Japan: “His massive purchases of bronzes, lacquerwares, embroideries, books and paintings later provided him with a vivid recollection of that interesting Japanese winter.” (Mitteldeutsche Lebensbilder, Magdeburg: Selbstverlag der Historischen Kommission für die Provinz Sachsen und für Anhalt, 1927, vol. 2, p. 411.)

From the possession of von Ballhausen stem fifty items, including several maps, landscape descriptions, illustrated books on legendary and historical persons, as well as several medicinal titles.

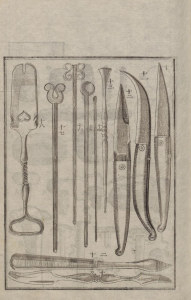

Yōka seisen zukai (瘍科精選図解)

n. d. (preface dated 1819 (Bunsei 2)), 2 booklets, 37641 ROA

The work shows mainly images of surgical instruments used in Western medicine with Japanese explanations added by Koshimura Tokuki (dates unknown). The illustrations are taken from the book “Chirurgie” [Surgery], published in 1719, authored by the eminent German surgeon and botanist, Lorenz Heister (1683-1758). This work was published in Germany in numerous editions, translated into several languages, and had a great influence on the introduction of Western medicinal techniques into Japan.

Page with surgical instruments of the Western practice of medicine in Yōka seisen zukai

Source: Booklet 1, no pagination, shelf mark: 37641 ROA

Murasaki shikibu genji karuta (紫式部源氏かるた)

1857 (Ansei 4), accordion fold book, 37647 ROA

The work Genji monogatari (源氏物語, The Tale of Genji) in 54 chapters, is the oldest Japanese novel, attributed to the court lady Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部, late 10th century/early 11th century). It provided the template for this work. The picture album with illustrations by the very successful artist Utagawa Kunisada II. (歌川国貞 2世, 1823-1880) accordingly contains 54 pictures, each of which carrying the title, artist’s name, editor and the stamp of censorship. As a matter of fact, however, what is shown are scenes from the parody Nise murasaki inaka genji (偐紫田舎源氏, A rural Genji by a fake Murasaki), which was published as a serial novel between 1829 and 1842 and was extremely popular. In the parody which is only loosely based on the original, the very tangled plot is transferred into the 15th century. As a consequence of this profusely illustrated novel, prints with Genji motives developed into a veritable fashion trend.

The illustration refers to chapter four, titled “Yūgao”. The main figure, the bon vivant Mitsuuji (in the original: Prince Genji), is standing on the right, with his hand on his sword, ready for defense. In front of him kneels his lover, Tasogare (in the original: Yūgao). She is wearing a Kimono with a pattern of bottle gourd blossoms. In Japanese, this plant is called yūgao, which suggests a connection to the identically-named figure in the original Genji Tale. Tasogare tries to protect herself with a bamboo curtain against the appearance of Akogi’s spirit. Akogi (in the original: court lady Rokujō) is a high-ranking courtesan and another lover of Mitsuuji who is incensed by the fact that he has gotten himself involved with Tasogare who is of a lower status. Next to Akogi’s supernatural appearance, there is a peonie lantern — botan dōrō in Japanese — which symbolises and identifies the figure as a ghost. This lantern is an allusion to one of the most famous Japanese ghost stories, with just exactly the same title, Botan dōrō.

Illustration of chapter 4 “Yūgao“ in the Murasaki shikibu genji karuta

Source: no pagination, shelf mark: 37647 ROA

Detail from the Hizen Nagasaki zu with the fan-shaped artificial island Deshima / Dejima

Source: shelf mark: 37614 ROA

Hizen Nagasaki zu (肥前長崎図)

approximately Ansei period (1854-1860), map 46,3 x 69,6 cm (folded 15,7 x 8,8 cm), 37614 ROA

The map shows harbour and city of Nagasaki, with information on the distance to some other Japanese cities. The map provides no grid or scale. In the section shown here, the fan-shaped artificial island Deshima / Dejima is clearly visible; there, the Dutch factory had been located, which was Japan’s window to Europe during the period of self isolation. Next to it, on a rectangular island, are the storage buildings of the Chinese merchants. Moreover, two Dutch vessels carry additional inscriptions, one of which is just firing salute.

Sources

Selected Bibliography About the persons ::: Brandt, Max von. Dreiunddreissig Jahre in Ost-Asien. Erinnerungen eines deutschen Diplomaten ; in drei Bänden. Leipzig: Wigand, 1901 (Vol. 1: Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien : Japan, China, Siam, 1860-1862 ; zurück nach Japan, 1862) ::: Dobson, Sebastian und Sven Saaler (Hg.). Unter den Augen des Preußen-Adlers : Lithographien, Zeichnungen und Photographien der Teilnehmer der Eulenburg-Expedition in Japan, 1860-61 = Under eagle eyes : lithographs, drawings & photographs from the Prussian expedition to Japan, 1860-61 = プロイセン・ドイツが観た幕末日本 : オイレンブルク遠征団が残した版画、素描、写真. München: Iudicium, 2011 ::: Eulenburg, Friedrich zu. Ost-Asien 1860 – 1862 in Briefen des Grafen Fritz zu Eulenburg, Königlich Preußischen Gesandten, betraut mit außerordentlicher Mission nach China, Japan und Siam / Hg. von Philipp zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld. Berlin: Mittler, 1900 ::: Lucius von Ballhausen, Robert. Selbstbiographie. Hg. von Frh. Hellmuth Lucius v. Stoedten. Görlitz : Hoffmann & Reiber, 1921 ::: Mitteldeutsche Lebensbilder. Hg. von der Historischen Kommission für die Provinz Sachsen und für Anhalt. Magdeburg: Selbstverlag der Historischen Kommission für die Provinz Sachsen und für Anhalt, 1926-1930, 5 Bde ::: Richthofen, Ferdinand von. Ferdinand von Richthofens Aufenthalt in Japan. Aus seinen Tagebüchern. In: Mitteilungen des Ferdinand-von-Richthofen-Tages 1912. Berlin: Reimer, 1912, pp. 19-185 ::: Schwalbe, Hans und Heinrich Seemann (Hg.). Deutsche Botschafter in Japan 1860-1973. Tōkyō: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens, 1974 (Mitteilungen der Deutsche Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens; 57)

About the works in the historical Japanese collection of the SBB-PK

::: Bartlett, Harley Harris. Hide Shohara. Japanese botany during the period of wood-block printing. Los Angeles : Dawson, 1961

:::『ベルリン東洋美術館』 平山郁夫、 小林忠編著 東京 : 講談社、1992(秘蔵日本美術大観 ; 7)

::: Hillier, Jack. Japanese prints : 300 years of albums and books. London : Brit. Museum Publ., 1983

::: Kraft, Eva. Illustrierte Handschriften und Drucke aus Japan. 12.-19. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1981

::: Kraft, Eva. Die Japansammlung der Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz. In: Bonner Zeitschrift für Japanologie, 3.1981, pp. 111-120

::: Kraft, Eva (Hg.). Japanische Handschriften und traditionelle Drucke aus der Zeit vor 1868 im Besitz der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin. Staatsbibliothek und Staatliche Museen: Kunstbibliothek mit Lipperheidischer Kostümbibliothek, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Museum für Völkerkunde. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1982 (Verzeichnis der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland ; XXVII,1)

::: Kraft, Eva. The Japanese collection in the ‚Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz‘ in Berlin. In: Japan Forum, 3.1991, Nr. 2, pp. 211-220

::: エヴァ・クラフト、北村浩、沢井耐三編者 『西ベルリン本お伽草子絵巻集と研究』 豊橋 : 未刊国文資料刊行会、1981 未刊国文資料 ; 第4期第10冊)

::: Mitchell, Charles H. The illustrated books of the Nanga, Maruyama, Shijo and other related schools of Japan ; A bibliography. Los Angeles : Dawson’s Book Shop, 1972

::: Toda, Kenji. Descriptive catalogue of Japanese and Chinese illustrated books in the Ryerson Library of the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago, 1931

About the East Asia Department

::: Kaun, Matthias. The East Asia Department of the Berlin State Library: German National Resource for East Asian material. In: 圖書館學與資訊科學 = Journal of library and information science, 33.2007, Nr. 2, pp. 9-18

::: Kaun, Matthias. Die Ostasienabteilung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. In: Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie, 54.2007, Nr. 2, pp. 59-66

::: Säuberlich, Wolfgang. Die Ostasienabteilung der Staatsbibliothek. In: Jahrbuch Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 1971, pp. 181-202

![Inscription on the cover of the bundle „Resumé der Conferenz mit den Gouverneuren am 18ten September 1860 in Jeddo“ [Summary of the meeting with the governors on the 18th September 1860 in Edo]](https://themen.crossasia.org/wp-content/uploads/Eulenburg_Hülle_Konvolut_Monjorui_Ausschnitt-300x193.jpg)

![Sales cover with the inscription “Dem Verfasser zugesandt durch den Gouverneur des Auswärtigen, Fürst Hori Oribe no kami” [Sent to the author by the Governor of the Exterior, Prince Hori Oribe no kami]](https://themen.crossasia.org/wp-content/uploads/Brandt_Sanpei_takuchiki_Verkaufshuelle_Zuschrift_Beschnitten_Kreis-1-247x300.jpg)

![Sales cover with the name „Heri [sic] Oribe no kami“](https://themen.crossasia.org/wp-content/uploads/Brandt_Sanpei_takuchiki_Verkaufshuelle_Hori_beschnitten_Kreis-1-246x300.jpg)